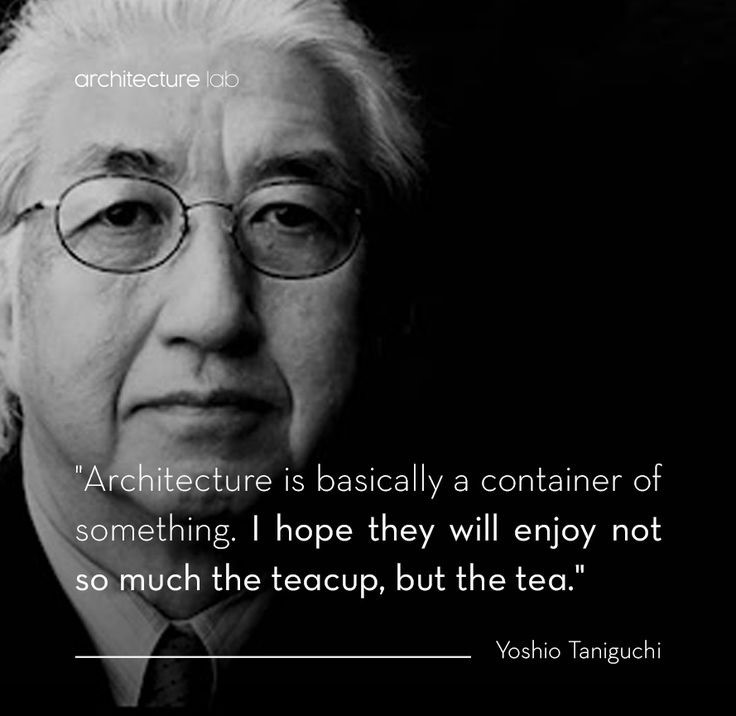

~ Yoshio Taniguchi Yoshio Taniguchi's adage, "Architecture is basically a container of something. I hope they will enjoy not so much the teacup, but the tea," is a profound statement that, when elaborated in terms of architecture, reveals his core design principles and values. It’s a call for architects to prioritize function, experience, and the …

~ Yoshio Taniguchi

Yoshio Taniguchi’s adage, “Architecture is basically a container of something. I hope they will enjoy not so much the teacup, but the tea,” is a profound statement that, when elaborated in terms of architecture, reveals his core design principles and values. It’s a call for architects to prioritize function, experience, and the human element over mere formal expression or stylistic flourish.

The Teacup: The Architect’s Craft and Formal Purity

In architectural terms, the “teacup” embodies the physical manifestation of the building. For Taniguchi, this means:

- Geometric Precision and Clarity: His buildings are characterized by impeccable geometry, clean lines, and rational compositions. There’s a deliberate lack of extraneous ornamentation; every element feels intentional and contributes to the overall clarity of the form. This isn’t austerity for its own sake, but a disciplined approach to creating a coherent and legible structure. Think of the crisp, almost crystalline volumes of his museums, where walls meet precisely and planes extend with unwavering precision.

- Mastery of Materials: Taniguchi was a master at selecting and deploying materials. He often favored a limited palette of high-quality, durable materials like concrete, glass, steel, and natural stone. The beauty of these materials is allowed to speak for itself, often through subtle variations in texture, finish, and the way light interacts with them. This meticulous approach to materiality is part of crafting a robust and elegant “teacup” that can withstand time and seamlessly integrate with its surroundings. The polished granite, the precisely fitted glass panels, or the exposed concrete of his buildings are not just structural components, but integral to their aesthetic and tactile presence.

- Control of Light: A hallmark of Taniguchi’s work is his exquisite control over natural light. He designs spaces where light is carefully modulated and filtered, creating a serene and contemplative atmosphere. This is achieved through strategic placement of windows, skylights, and screens, as seen in the top-lit galleries of MoMA or the subtle illumination of the Gallery of Horyuji Treasures. The “teacup” is sculpted by light, using it not just for illumination but as an active element in shaping space and mood. This light control enhances the “tea” by revealing its nuances and creating the perfect viewing conditions.

- Seamless Detailing: Taniguchi’s commitment to the “teacup” also extends to an almost obsessive attention to detail. Joints are minimized, connections are concealed, and services are often integrated invisibly. This level of refinement ensures that the architectural elements themselves recede, allowing the overall form and the experience within to take precedence. As he reportedly said regarding MoMA, “Raise a lot of money for me, I’ll give you good architecture. Raise even more money, I’ll make the architecture disappear.”1 This implies that the perfection of the “teacup” allows it to fade into the background, focusing attention on the “tea.”

The Tea: The Inhabited Experience and Functional Enrichment

The “tea” is where Taniguchi’s architecture truly lives and breathes. It’s the human-centric purpose of the building, and how the “teacup” facilitates and enriches it. In architectural terms, this translates to:

- Prioritizing the Content and User: For a museum, the “tea” is the art and the visitor’s engagement with it. Taniguchi’s galleries are designed to be neutral, yet powerfully atmospheric backdrops that allow the artworks to be the primary focus. He understands that crowded or distracting spaces detract from the contemplation of art. His spacious layouts, logical flow, and unobtrusive details ensure that the visitor’s journey through the exhibition is seamless and rewarding. The architecture doesn’t shout; it whispers, guiding the eye and the body.

- Enhancing Functionality and Flow: Beyond aesthetics, Taniguchi’s “teacups” are highly functional. Circulation paths are clear, intuitive, and often punctuated by carefully framed views to the outside or to other parts of the building. This creates a sense of orientation and ease, minimizing cognitive load for the user. In the MoMA expansion, for instance, his design opened up previously cramped spaces, created clear vertical circulation, and restored the Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Sculpture Garden as a central organizing element, vastly improving the visitor experience.

- Creating Contemplative Environments: Many of Taniguchi’s projects are cultural institutions (museums, art houses). He designs spaces that foster a sense of tranquility, introspection, and quiet engagement. The calm, ordered nature of his “teacups” helps to prepare the mind for the “tea” – whether it’s viewing art, studying historical artifacts, or simply reflecting. The deliberate control of scale, light, and sound within his spaces contributes to this sense of calm.

- Respect for Context, Internal and External: While his forms are often minimalist, Taniguchi doesn’t design in a vacuum. His “teacups” are designed to be sensitive to their internal context (the collection they house) and their external environment. At MoMA, he acknowledged the urban context of Midtown Manhattan while still creating serene interior worlds. In his Japanese projects, he often integrated elements of the natural landscape, blurring the boundaries between interior and exterior and allowing nature to become part of the “tea” experience.

The Interplay: Teacup and Tea as an Inseparable Whole

Taniguchi’s genius lies in understanding that the “teacup” and the “tea” are not separate entities, but rather mutually reinforcing aspects of a successful architectural experience. A poorly designed “teacup” (a distracting or dysfunctional building) would diminish even the finest “tea.” Conversely, a well-crafted “teacup” (a serene, functional, and aesthetically pleasing space) elevates the “tea” to a higher level of enjoyment.

His philosophy is a subtle critique of architecture that prioritizes form over function, or spectacle over substance. It advocates for an architecture that is humble yet powerful, understated yet deeply impactful. The goal is not to be admired for the building itself, but for the profound experiences it enables and the rich content it so gracefully contains. For Taniguchi, the architect is the silent enabler, crafting the perfect vessel so that the human spirit within can truly flourish.