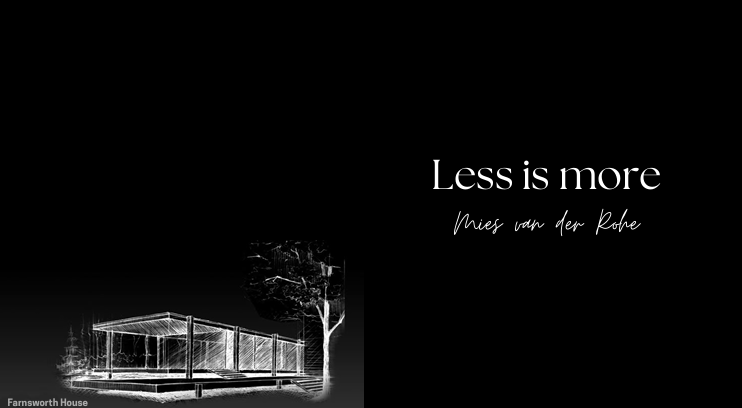

~Mies Van der Rohe Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, a titan of 20th-century architecture, distilled his revolutionary philosophy into four potent words: "Less is More." This declaration, far more than a simple aesthetic preference, became a defining credo of Modernism, advocating for a radical stripping away of the superfluous to reveal the inherent beauty and …

~Mies Van der Rohe

Table of Contents

- The Genesis of a Credo: Modernism and the Pursuit of Essence

- Deconstructing “Less”: The Art of Subtraction

- Deconstructing “More”: The Amplification of Experience

- Mies’s Masterpieces: Embodiments of the Maxim

- Criticisms, Nuances, and the Paradox of Minimalism

- Enduring Relevance in Contemporary Architecture

Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, a titan of 20th-century architecture, distilled his revolutionary philosophy into four potent words: “Less is More.” This declaration, far more than a simple aesthetic preference, became a defining credo of Modernism, advocating for a radical stripping away of the superfluous to reveal the inherent beauty and truth of structure, material, and space. For an architect, “Less is More” is a constant challenge, an invitation to disciplined thinking, and a profound aspiration to achieve maximum impact with minimal means. It is a philosophy that, when truly understood and applied, transcends mere style to become a pathway to clarity, efficiency, and timelessness in the built environment.

This essay will delve into the profound implications of “Less is More” from an architect’s perspective, exploring its historical context, dissecting the true meaning of both “less” and “more,” examining how Mies himself manifested this philosophy in his iconic works, and considering its enduring relevance and nuanced interpretations in contemporary practice.

The Genesis of a Credo: Modernism and the Pursuit of Essence

To fully appreciate “Less is More,” one must understand the architectural landscape from which it emerged. The early 20th century was a period of immense social, technological, and cultural upheaval. Architects, like Mies, were reacting against the historical revivalism and excessive ornamentation that characterized much of the 19th-century architecture. They saw it as dishonest, wasteful, and irrelevant to the demands of an industrializing, rapidly changing world.

Modernism sought a new architectural language rooted in function, structure, and the inherent qualities of new materials like steel, concrete, and glass. The mantra “Less is More” became a concise articulation of this revolutionary spirit. It wasn’t about austerity for its own sake, but about a deliberate act of reduction, a rigorous intellectual process of stripping away the inessential to reveal the inherent potential and beauty of space and form. It was a call for purity, clarity, and an uncompromising honesty in design.

Deconstructing “Less”: The Art of Subtraction

For an architect, “less” does not imply laziness or a lack of detail; rather, it demands a higher degree of precision, a deeper understanding of fundamentals, and a more intense focus on the essential.

- Elimination of Ornamentation: The most immediate interpretation of “less” is the rejection of applied decoration and historical stylistic motifs. Mies believed that ornamentation distracted from the true essence of a building. He advocated for a return to fundamental architectural elements: the wall, the column, the floor, the roof. This wasn’t a Puritanical stance against beauty, but a belief that beauty should emerge organically from the structure, materials, and spatial relationships themselves. The form should express its purpose and construction, rather than being adorned.

- Reduction to Essence: “Less” means distilling a design down to its core components. It asks: What is truly necessary for this space to function, to feel, and to exist? This process involves rigorous questioning and a disciplined approach to every design decision. Every line, every plane, every volume must justify its existence. This often leads to simple geometries, rectilinear forms, and clear, uncluttered compositions. The building becomes a container for life, rather than a decorative object.

- Clarity and Purity: By removing visual noise, “less” achieves clarity. The structural system becomes legible, the flow of space is unobstructed, and the qualities of materials are allowed to speak for themselves. This purity creates a sense of calm and order, allowing the inhabitant to focus on the experience of the space itself, rather than being overwhelmed by unnecessary visual information.

- Efficiency and Economy (of Means, not necessarily Cost): “Less” can also imply efficiency in construction and resource use. By simplifying forms and standardizing components, buildings could be constructed more economically and with greater speed, reflecting the industrial processes of the era. However, it’s crucial to note that Mies’s minimalism often demanded incredibly precise detailing and high-quality materials, which could be expensive. Thus, “economy” referred more to an intellectual rigor and clarity of means than necessarily low cost. The focus was on doing more with less effort or superfluous elements.

Deconstructing “More”: The Amplification of Experience

The true power of Mies’s aphorism lies in the second half: “is More.” The act of subtraction is not an end in itself, but a means to achieve a heightened, richer, and more profound architectural experience. When the unnecessary is removed, what remains is amplified and celebrated.

- More Clarity and Legibility: A simple, uncluttered design is easier to understand and navigate. The functional layout becomes immediately apparent, and the relationship between different spaces is clear. This legibility enhances user experience and reduces cognitive load, allowing people to feel more comfortable and confident in the environment.

- More Enhanced Spatial Experience: This is perhaps the most significant “more.” By stripping away walls, reducing visual barriers, and maximizing transparency, Mies created spaces that flow seamlessly, often extending beyond the physical confines of the building into the surrounding landscape. The Barcelona Pavilion, with its non-load-bearing walls and expansive glass, is a quintessential example of this. The experience is one of continuous, unencumbered space, where light and air move freely. This fluidity creates a dynamic and immersive environment, allowing the spatial volume itself to become the primary expressive element.

- More Truth to Materials and Structure: When ornamentation is eliminated, materials and structural elements are forced to stand on their own. Their inherent beauty – the grain of stone, the sheen of steel, the texture of concrete, the transparency of glass – becomes the sole decorative element. This honesty in material expression creates a sense of authenticity and integrity, allowing the building to speak plainly about its construction and composition. The exposed I-beams of the Seagram Building are a prime example of structure being celebrated for its inherent aesthetic quality.

- More Focus on the Human Element: When the architecture recedes into a background of pure forms and noble materials, the human activity within the space comes to the forefront. The inhabitants, their movements, interactions, and the objects they bring into the space, become the primary focal points. The building becomes a meticulously designed stage upon which human life unfolds, allowing for individual expression and the celebration of human presence. The open, flexible plans championed by Mies allow for diverse arrangements and adaptations by the users, empowering them rather than dictating their every move.

- More Timelessness and Adaptability: Simplicity and purity often lead to timeless designs. Buildings that avoid stylistic fads and rely on fundamental principles tend to age more gracefully and remain relevant across generations. Furthermore, unencumbered, flexible spaces are inherently more adaptable to changing needs and technologies. A simple, modular structure can accommodate various uses over time, making it sustainable in a pragmatic sense.

- More Heightened Sensory Perception: The absence of clutter allows the other senses to come alive. The quality of light takes on a dramatic presence, highlighting textures and defining volumes. The subtle sounds within a quiet, uncluttered space become more noticeable. The tactile qualities of carefully chosen materials are amplified. The precise detailing and construction become evident, revealing the craftsmanship and intellectual rigor behind the design. “Less is More” creates an environment where every sensory input is intentionally orchestrated and deeply felt.

Mies’s Masterpieces: Embodiments of the Maxim

Mies van der Rohe’s own architectural works stand as the most eloquent demonstrations of “Less is More.”

- The Barcelona Pavilion (1929): A quintessential example. With its free-standing walls of marble and onyx, chrome-plated columns, and expansive glass, the pavilion is not a building in the traditional sense, but a composition of planes defining flowing space. There is no applied ornament. The “less” (minimal walls, no fixed program, pure forms) creates “more” (an incredibly rich sensory experience, a profound dialogue between inside and outside, a celebration of luxurious materials, and a sense of infinite spatial extension).

- The Seagram Building (1958): A monumental skyscraper in New York, the Seagram Building embodies the “less is more” principle in an urban context. Its minimalist glass and bronze facade, with exposed I-beams, celebrates structural expression. The building’s precise proportions, the carefully designed plaza, and the clarity of its form create an overwhelming sense of dignity and timeless presence. The “less” of ornament and stylistic flourish yields “more” in terms of iconic urban statement and a powerful sense of order amidst the city’s chaos.

- The Farnsworth House (1951): This glass and steel pavilion suspended above the Fox River is an extreme expression of transparency and minimal enclosure. The “less” of solid walls and defined rooms results in “more” connection to nature, an almost spiritual communion with the landscape. The house becomes a frame through which to experience the ever-changing environment, blurring the boundaries between interior and exterior. Its pure, unadorned form highlights the beauty of industrial materials and the precise elegance of its construction.

Criticisms, Nuances, and the Paradox of Minimalism

While “Less is More” has been immensely influential, it has also faced criticism and requires careful interpretation.

- Potential for Coldness and Sterility: In less skilled hands, a dogmatic application of “Less is More” can lead to sterile, uninviting, or even alienating spaces. When purity becomes rigidity, and minimalism is mistaken for emptiness, buildings can lack warmth, human scale, or the richness that many people crave. The human element, which Mies sought to amplify, can sometimes be overshadowed if the design is too stark or impersonal.

- The Hidden Complexity: Ironically, achieving “less” often requires “more” sophisticated engineering, precise detailing, and higher-quality materials. The seamless joints, flush surfaces, and apparent effortlessness of Mies’s buildings demanded extraordinary technical skill and meticulous craftsmanship. The “less” the viewer sees, the “more” goes into the hidden infrastructure and refined connections. This makes truly successful “less is more” architecture inherently complex to execute and often costly.

- Dogmatism vs. Philosophy: The phrase can be misunderstood as a rigid rule rather than a guiding philosophy. Mies himself was deeply concerned with universal architectural principles, not just a particular aesthetic. “Less is More” is a mindset about essentialism and honesty, not a prescriptive style for all contexts or functions.

Enduring Relevance in Contemporary Architecture

Despite its origins in a specific historical context, “Less is More” remains profoundly relevant for architects today, albeit with evolving interpretations.

- Sustainability and Resource Efficiency: In an era of climate crisis, the principle of “doing more with less” is critical. This translates to minimizing material consumption, reducing waste, optimizing energy performance, and designing for longevity and adaptability. A building that is rigorously efficient in its form and material use embodies the spirit of “Less is More” in an ecological sense.

- Functionality and Usability: Clutter-free, clearly organized spaces are inherently more functional and user-friendly. In complex building types like hospitals, airports, or educational institutions, clarity and legibility are paramount for efficient operation and user comfort. “Less is More” promotes a human-centered approach to functionality.

- Wellness and Mental Clarity: In an increasingly complex and noisy world, spaces that offer simplicity, calm, and a sense of order can contribute significantly to mental well-being. The uncluttered aesthetic, generous natural light, and quiet dignity of minimalist spaces can provide a respite from sensory overload, fostering focus and tranquility.

- Beyond Style: “Less is More” has transcended its origins in Modernism to become a universal design principle. Architects working in diverse styles, from biophilic to parametric, can still apply the core tenets of essentialism, efficiency, and clarity to their work. It encourages a critical examination of every element, ensuring that each contributes meaningfully to the overall design intent.

“Less is More” is not a call for impoverished design, but a profound challenge to architects to achieve richness through restraint. It is a philosophy that demands intellectual rigor, an uncompromising commitment to fundamental principles, and a deep understanding of how space, light, and material profoundly affect human experience. When an architect successfully embodies this maxim, they create buildings that are not merely functional or aesthetically pleasing, but powerful, timeless, and capable of shaping us in meaningful and enduring ways.

In the hands of a master like Mies van der Rohe, “Less is More” transcended a stylistic choice to become a moral imperative – an ethical stance against excess and a celebration of truth in construction. It reminds us that greatness in architecture often lies not in what is added, but in what is carefully, thoughtfully, and purposefully removed, allowing the essential spirit of the building to emerge and resonate with profound power. It is a timeless pursuit, continually pushing architects to refine their vision, simplify their forms, and ultimately, amplify the human experience within the built environment.