~Tadao Ando Architecture, in its purest form, is a dialogue a conversation between human intention and the natural world. When Tadao Ando said, “We borrow from nature the space upon which we build,” he wasn’t merely being poetic. He was reminding us, as architects, of a deep truth: that the land we shape is never …

~Tadao Ando

Table of Contents

- The Philosophy of Borrowing Space

- Tadao Ando: The Man and the Method

- Nature as Site, Subject, and Spirit

- Case Study: Chichu Art Museum (Naoshima, Japan)

- How Architects Can Learn to Borrow

- Not Imitation, but Integration

- Urban Contexts: Borrowing in the City

- Legacy and Continuing Influence

- Conclusion

- Concept and Design Approach

- Spatial Experience

- Materiality and Integration with Nature

- Borrowing, Not Taking

- Architectural Lessons

- Conclusion

Architecture, in its purest form, is a dialogue a conversation between human intention and the natural world. When Tadao Ando said, “We borrow from nature the space upon which we build,” he wasn’t merely being poetic. He was reminding us, as architects, of a deep truth: that the land we shape is never truly ours. We are stewards, not owners. Our responsibility is not to impose upon nature, but to respond to it, to respect its presence, to design in harmony with its rhythms.

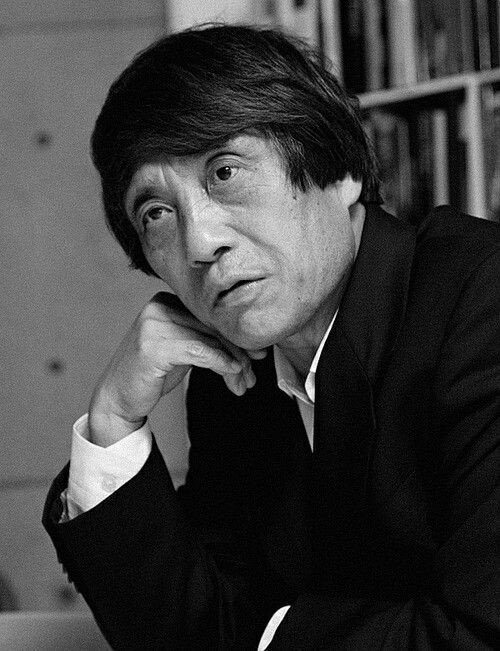

Tadao Ando- the Zen master of concrete

Tadao Ando, one of the most influential architects of the 20th and 21st centuries, has made a career of doing precisely that. A self-taught master of minimalism and light, Ando’s architecture is often seen as austere at first glance bare concrete walls, stark geometry, disciplined compositions. But look again, and you’ll find something else entirely: sensitivity, serenity, and a profound respect for the site. His buildings don’t conquer landscapes; they frame them. They don’t replace nature; they reveal it. He teaches us that architecture does not compete with nature it completes it.

The Philosophy of Borrowing Space

To borrow space is to acknowledge that it is not ours. This idea contrasts with the typical development mindset that treats land as a commodity to be bought, sold, and built upon with impunity. Instead, Ando proposes humility. Nature existed long before our arrival, and it will endure long after. When we build, we interrupt. When we construct, we alter. But if we are thoughtful, we can do so gently, meaningfully.

“Borrowing” implies responsibility. When we borrow something, we are expected to return it in good condition ideally, better than we found it. This ethic of design echoes sustainable and regenerative practices. It asks: Will this building honor the land it occupies? Will it allow light and wind and water to continue their paths? Will it connect people more deeply with the nature around them?

For Ando, architecture must operate like a haiku concise, deliberate, and in tune with nature. His buildings are often deeply minimalist, not because they lack ideas, but because they distill many ideas into one powerful spatial experience. Nature is always present in his architecture not always in greenery, but in light, shadow, breeze, reflection, and silence.

Tadao Ando: The Man and the Method

Born in Osaka, Japan in 1941, Ando began his career not in design school, but in boxing rings. He was a professional boxer before teaching himself architecture by traveling, reading, and sketching. He visited temples, churches, and traditional buildings around the world, developing an eye for spatial composition and a mind rooted in both Eastern philosophy and Western modernism.

His design language combines Zen simplicity with modernist precision. His material of choice is often smooth, poured-in-place concrete, used not as a cold industrial medium, but as a canvas for light. He pairs this with water, sky, and vegetation to create spaces that are as meditative as they are functional. His buildings whether religious, residential, or public create silence and stillness that allows the presence of nature to emerge.

Nature as Site, Subject, and Spirit

In Ando’s work, nature is not just background it’s protagonist. He doesn’t merely site buildings in nature; he sites them with nature. Every tree, hill, breeze, and beam of light is treated as an active participant in the experience of space.

Take, for instance, his famous Church of the Light (1989) in Ibaraki, Japan. The building is strikingly simple a rectangular concrete box sliced by a cross-shaped void at the altar wall. That cross is not symbolic alone; it is real, filled with natural light that pours in each morning. There are no stained-glass windows or lavish decoration.

The Church of Light

The light itself becomes the sacred element. Here, Ando borrows not just the land but the very phenomena of the earth sunlight, silence, shadow to create a deeply spiritual space.

In another iconic project, The Water Temple (Hompu-ji, 1991) in Awaji Island, visitors arrive not at the building, but at a lotus pond. The architecture is hidden below the water. A staircase bisects the pond, leading down into a world of concrete and reflection.

The Water Temple-Honpukuji, Awaji Island, Japan

The movement from surface to depth mirrors spiritual introspection. Nature is not ornamental; it is integral to the sequence of experience. The temple is not simply in the landscape it is the landscape, shaped by and shaping the visitor’s perception of nature.

Case Study: Chichu Art Museum (Naoshima, Japan)

If one project epitomizes Ando’s philosophy of borrowing from nature, it is the Chichu Art Museum, built in 2004 on Naoshima Island. The name “Chichu” literally means “in the earth,” and the building is just that—buried into a hillside to minimize visual disruption to the island’s pristine scenery.

Chichu Art Museum, Japan

From the outside, the museum is barely visible. There are no grand facades, no skyline interruptions. It respects the natural topography, sinking into the earth rather than rising above it. Inside, the museum is an interplay of underground light, concrete geometries, and framed views of the sky. Natural light is the primary medium filtered through precisely angled openings to illuminate works by Claude Monet, James Turrell, and Walter De Maria.

This is where Ando’s genius lies: the architecture recedes so that both art and nature can come forward. Visitors don’t just view art they experience it in changing light, silence, and spatial intimacy. The building’s environmental control relies on passive methods: insulation by earth, daylighting, and the regulation of temperature via the ground itself. It is sustainable by design, but more importantly, it is poetic by intention.

Ando doesn’t just borrow land here he borrows the cosmos. The museum feels celestial, timeless. Visitors descend into the ground but emerge into a heightened awareness of light, sky, and perception. It’s not a museum about nature. It is nature sculpted, filtered, distilled.

How Architects Can Learn to Borrow

For today’s architects, Ando’s quote is more than philosophy it’s a call to action. In a time of climate crisis, urban expansion, and increasing disconnection from the natural world, we must re-evaluate our relationship to land. Borrowing from nature means several things:

- Design with humility

Before we draw, we must listen. Study the site the contours, sunlight paths, prevailing winds, existing vegetation, and views. Let the site suggest the design, not the other way around.

Museum SAN—Where Space, Art, and Nature Unite

- Create minimal impact

Like Ando’s Chichu Museum, buildings can blend with topography instead of overriding it. Structures can respect trees rather than remove them. They can harvest light and water instead of blocking or diverting them.

Chichu Museum

- Use materials that resonate with place

Concrete in Ando’s hands becomes soft and tactile, often complementing the earth it sits on. Local stone, reclaimed wood, or renewable materials not only lower environmental impact but feel “belonging” to their context.

- Let nature enter the architecture

Light, wind, and shadow should move through buildings, animating them. Openings should frame views, not just provide ventilation. Courtyards, verandas, and transition spaces become essential, not optional.

The hill of the Buddha

- Design for stillness and awareness

Architecture should not always stimulate; it should sometimes quiet. Ando’s spaces invite contemplation. By reducing noise visual or acoustic we heighten awareness of the natural.

The Quiet Icon

Not Imitation, but Integration

It’s important to note that Ando never suggests copying nature or turning buildings into faux-organic shapes. He’s not interested in architecture looking like nature. He’s interested in architecture belonging to nature.

This is why his minimalist, concrete buildings seemingly industrial can feel more in harmony with their landscapes than ornate, so-called “organic” buildings. He uses geometry to contrast and highlight nature. A rectangular window cut into a wall frames a single tree. A smooth concrete surface makes ripples on a pond more noticeable. By simplifying the built form, he allows the complexity of nature to speak louder.

Urban Contexts: Borrowing in the City

Even in dense cities, Ando’s philosophy applies. In urban projects like the Row House in Sumiyoshi (Azuma House, 1976), he designed a narrow concrete house with a central open courtyard exposed to the sky.

Row House in Sumiyoshi (Azuma House, 1976),

Though surrounded by buildings, the residents experience light, air, and rain as part of their daily life. It’s not about greenwashing or adding rooftop gardens it’s about genuine connection to elemental forces, even in the most compact footprint.

Legacy and Continuing Influence

Ando’s legacy goes beyond his buildings. His work is a blueprint for a more respectful architectural practice one that doesn’t dominate nature but enters into a partnership with it. In the age of sustainability, architects often look for technical solutions. Ando reminds us that sustainability also comes from spirit from the decision to borrow, not take.

His influence can be seen in architects around the world who embrace site-sensitive, poetic minimalism:

- Peter Zumthor, with his thermal baths in Vals.

- Kengo Kuma, who uses light wood and texture to dissolve boundaries between building and landscape.

- Glenn Murcutt, who designs “touch the earth lightly” homes in Australia.

All these architects understand that nature is not an inconvenience it is the origin of architecture.

Conclusion

“We borrow from nature the space upon which we build.” It is a statement of humility, of reverence, of shared existence. Tadao Ando’s architecture is not a style, but a stance one that acknowledges the land as sacred, the materials as storytellers, and the light as a co-designer.

As architects, we must remember that every site we touch carries a story before us. Our role is not to overwrite that story, but to listen, to collaborate, and to write the next chapter with care. In borrowing space from nature, we also inherit its responsibility: to build not only with intelligence but with grace. To create not monuments to ourselves, but homes for life to unfold quietly, beautifully, and in balance with the world that sustains us.

The Chichu Art Museum, located on Naoshima Island in Japan’s Seto Inland Sea, is a landmark project by Tadao Ando that embodies his philosophy of harmony between architecture and nature. “Chichu” literally translates to “in the earth,” and the museum lives up to this name: the majority of the structure is buried underground to preserve the island’s natural landscape and avoid disturbing its serene coastal setting.

This approach transforms the museum into more than a gallery for art it becomes an experience of the earth itself, where light, shadow, and elemental forces are the true curators.

Concept and Design Approach

Ando’s goal was to create a space where art, architecture, and nature exist in a state of balance. Rather than imposing a large building on the island, he allowed the topography to remain visually untouched. The architecture is largely invisible from a distance, revealing itself only as visitors approach and descend into the earth.

The museum is organized as a series of interconnected subterranean spaces, illuminated almost entirely by natural light. Openings, courtyards, and carefully angled skylights bring the sky and sunlight into the museum, creating ever-changing atmospheres throughout the day. The light itself becomes a dynamic “material,” altering how visitors perceive both the space and the artworks.

Spatial Experience

The museum is not a traditional sequence of galleries. Instead, it unfolds as a journey:

- Visitors move through stark concrete corridors that lead to sunken courtyards.

- Light pours in from above, often the only visible connection to the outside world.

- Views of the sky are framed by precise geometric openings, turning the heavens into a living artwork.

The galleries are purpose-built for a small selection of artists, including Claude Monet, James Turrell, and Walter De Maria. Each artwork interacts directly with natural light Monet’s Water Lilies series, for example, is displayed in a skylit room where the paintings shift subtly as sunlight changes, echoing Monet’s fascination with light and nature.

Materiality and Integration with Nature

The museum primarily uses smooth, cast-in-place concrete Ando’s signature material along with glass and steel. These materials provide a neutral, contemplative backdrop that amplifies the presence of light and landscape. By embedding the museum into the hillside, Ando achieves several layers of integration:

- Visual continuity: The island’s natural silhouette is preserved.

- Environmental performance: The earth acts as insulation, reducing energy needs.

- Experiential impact: Visitors feel as though they’re entering a different realm, retreating from the world above into a meditative space shaped by nature.

Borrowing, Not Taking

Ando doesn’t “occupy” the land so much as weave within it. The Chichu Museum borrows the hillside its coolness, its shelter, its silence and gives it back by remaining largely hidden, almost deferential to its surroundings. The natural elements are not decorations but active participants:

- Skylights channel sunlight like a sculptor channels form.

- Courtyards frame patches of sky as if they were paintings.

- The progression through darkness and light mirrors the shifting rhythms of the natural world.

Architectural Lessons

From an architect’s perspective, the Chichu Museum offers several insights into Ando’s philosophy and practice:

- Respect for topography: Buildings don’t always need to rise above the land to be powerful. Submerging or blending can create equally strong, often more poetic, experiences.

- Light as a design material: Natural light can define form and emotion more profoundly than artificial effects.

- Minimalism as a frame for nature: By stripping away excess, architecture can amplify the richness of the surrounding environment.

- Long-term stewardship: Designing with minimal visual and ecological disruption ensures that the landscape can endure alongside the building.

Conclusion

The Chichu Art Museum is more than a museum; it is a meditation on how humans can inhabit nature without overwhelming it. It exemplifies Tadao Ando’s belief that we only borrow the space we build upon that our interventions should heighten our connection to the land rather than sever it. By sinking into the earth, framing the sky, and choreographing light, Ando creates a space where visitors don’t just see art, they feel the quiet continuity of nature itself.