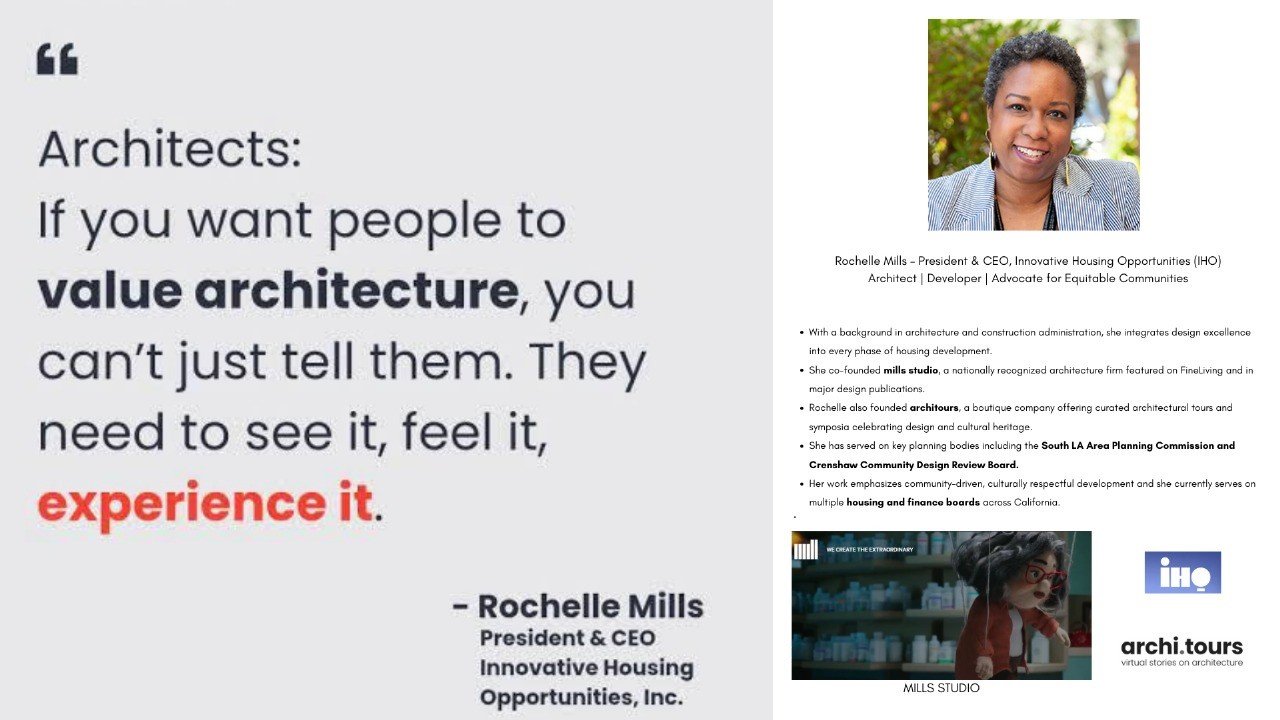

~Rochelle Mills While not a globally famous “starchitect,” Rochelle Mills is an architect, entrepreneur, educator, and civic leader whose work bridges design, housing justice, and cultural storytelling. As President & CEO of Innovative Housing Opportunities (IHO) in Southern California, she’s shaped hundreds of affordable housing units with dignity and creativity behind their architecture. Previously founding …

~Rochelle Mills

While not a globally famous “starchitect,” Rochelle Mills is an architect, entrepreneur, educator, and civic leader whose work bridges design, housing justice, and cultural storytelling. As President & CEO of Innovative Housing Opportunities (IHO) in Southern California, she’s shaped hundreds of affordable housing units with dignity and creativity behind their architecture.

Previously founding mills studio, featured in home design media, she’s also an educator at UCLA and Otis College, and former editor of LA Architect magazine. Her practice emphasizes that spatial design matters—not just for aesthetics, but for equity and belonging. Ames Mills often says architecture must be experienced emotionally and physically to be understood—not just argued from a boardroom.

From an architect’s perspective, this statement is both a reminder and a challenge. It reminds us that architecture, unlike many other arts, is inherently experiential. You cannot understand the proportions of a space, the warmth of sunlight streaming into a courtyard, or the intimacy of a quiet alcove by looking at a floor plan or a photograph. These experiences are multi-sensory they involve the way materials feel under your fingers, the acoustics of a busy plaza, the cool shade beneath a tree, and the emotional weight of walking into a space that feels safe, inspiring, or sacred. It also challenges architects to design spaces that offer these experiences naturally, so people can understand the value of architecture without explanation. Good design, after all, speaks for itself.

Architecture is not simply visual; it is haptic, acoustic, thermal, and emotional. A corridor can evoke warmth and safety through its lighting and materials. A courtyard can feel alive when sunlight animates its edges and the sound of children playing echoes off its walls. A simple material choice a rough brick that carries the memory of local craft or a smooth, cool stone floor that brings relief on a hot summer day can create an emotional connection stronger than any description could achieve. For Mills, whose work often deals with communities that have been overlooked or underserved, these sensory and emotional qualities are not luxuries. They are essential tools for making residents feel valued, respected, and truly at home.

The quote also highlights the difference between telling and showing. Architecture cannot be sold solely through words or technical presentations; its value must be felt. A thoughtfully designed affordable housing complex, for example, may include courtyards that encourage social interaction, shaded paths that offer comfort, and spaces that give residents pride and ownership. These qualities cannot be communicated through a brochure alone. They are understood when a visitor sees families gathering in the courtyard, feels the breeze moving through an open corridor, and senses the dignity embedded in the materials and proportions. When people experience these qualities firsthand, they instinctively understand why architecture matters.

Architecture, in many ways, educates people about itself through the experiences it creates. A person may not know the technical term for a skylight, but they understand the uplifting feeling of natural light spilling into a room. They may not be able to articulate the acoustic properties of a plaza, but they feel the energy when the sound of life animates the space. As architects, our job is to design spaces that speak this intuitive language. We must remember that people connect with architecture through how it makes them feel safe, inspired, awed, comforted not through its technical specifications.

Several elements help architecture achieve this level of experiential resonance. Scale and proportion, for example, shape how people relate to a space. A human-scaled entrance feels inviting, while a soaring atrium can inspire awe and a sense of occasion. Materials and textures also play a crucial role. Reclaimed brick can evoke history and authenticity, while polished concrete or warm timber can speak of modernity or comfort. Light and shadow guide emotions soft, diffused light can soothe, while dramatic shafts of sunlight can uplift or dramatize a moment. Movement and surprise, too, are powerful tools. Architecture is a journey, not a static object, and the way spaces unfold through framed views, changing ceiling heights, or sudden transitions from darkness to light creates memories that last far longer than the sight of a façade.

Examples of architecture that embody Mills’s philosophy abound. Many of the affordable housing projects designed under her leadership at Innovative Housing Opportunities, for instance, use thoughtful layouts and materials to create communities that feel dignified and alive. Shared courtyards encourage social interaction. Quality finishes, even within budget constraints, communicate care and value. Residents often report that living in these spaces makes them feel respected a feeling that cannot be captured in a project summary but is felt in every corner of the development. People leave such spaces with a deeper understanding of what good architecture can do for their lives.

This idea is not limited to Mills’s own projects. Tadao Ando’s Church of the Light, for example, can be described in a single sentence: a concrete chapel with a cross cut into the wall, letting in light. But no description can replace the experience of sitting inside as sunlight streams through that cross, creating a moment of spiritual connection that transcends words. Similarly, Frank Lloyd Wright’s Fallingwater can be summarized as a house cantilevered over a waterfall, but its true power is felt when you stand on its terraces, hear the roar of water beneath your feet, and feel the structure becoming one with the landscape around you. These are moments where architecture bypasses explanation and communicates directly to the senses.

Adaptive reuse projects provide another clear example. When an old factory is transformed into a cultural center, the worn columns, weathered brick, and echoes of its industrial past tell stories that no brochure or plaque could communicate. Visitors don’t just read about the history; they inhabit it. The tactile and spatial qualities of the architecture make the past present, connecting people to a deeper cultural narrative.

For architects, Mills’s quote is also a directive: design spaces from the inside out, focusing on the user’s sensory journey. Rather than starting with an external form or a trend-driven image, begin by imagining how people will move through, touch, and perceive the space. Walk the site to understand its qualities. Prototype critical elements doorways, corners, seating areas to test how they feel. Use narratives, not just diagrams, to communicate design: describe how a grandmother might sit by a window reading, or how a child might feel safe playing in a courtyard. These human stories help clients, communities, and users understand the value of architecture even before it is built.

Measuring the success of architecture should extend beyond efficiency and budgets. While metrics like energy performance and cost are essential, architects should also gather emotional feedback. Do residents feel safe? Do they socialize in shared spaces? Do they feel pride in their surroundings? These qualitative aspects reflect whether architecture is truly being valued and whether it is achieving its deeper purpose.

However, creating architecture that can be seen, felt, and experienced is not without challenges. In a development-driven world, architecture is often reduced to a commodity, with decisions driven by cost per square foot or marketability rather than quality of experience. In these contexts, it is even more critical for architects to advocate for design through direct engagement. Organizing site visits to successful precedents, building mock-ups, or creating immersive visualizations can help clients and stakeholders understand the power of good design not through lectures, but through lived moments.

Ultimately, Rochelle Mills’s quote reminds us that architecture is a silent teacher. It does not need to convince through arguments or jargon when it is designed with care and empathy. People remember how a space made them feel the warmth of sunlight, the comfort of proportions, the texture of a wall beneath their fingers long after they forget the architect’s name or the project’s budget. This is where the value of architecture lies: in the experiences it creates and the lives it enhances.

For architects, this is both an inspiration and a responsibility. We are not simply designing buildings; we are shaping the environments where life unfolds. We are crafting spaces that, if done well, will make people feel something profound something that connects them to place, to others, and to themselves. And when people feel this connection, they will value architecture not because someone told them to, but because they have lived it. They have seen it, felt it, and experienced it and that is when architecture truly becomes meaningful.