CopenHill: When Architecture Climbs Above Function In the harbor district of Copenhagen stands a building that simultaneously burns trash and breaks expectations. Officially known as Amager Bakke (but far better known as CopenHill), this waste-to-energy plant slash urban recreation center is one of the most radical and imaginative pieces of architecture of the 21st century. …

Table of Contents

- CopenHill: When Architecture Climbs Above Function

- The Big Idea: Hedonistic Sustainability

- Site & Context: The Industrial Edge of the City

- Architecture as Infrastructure

- The Form

- The Ski Slope: Urban Playground Meets Alpine Ambition

- Beyond Skiing: Climbing, Hiking, and More

- The Façade: Function and Expression

- Energy Production

- Carbon Footprint

- Biodiversity & Ecology

- CopenHill in Pop Culture & Global Discourse

- A Blueprint for Future Cities?

- Conclusion: Upending Expectations, Literally

CopenHill: When Architecture Climbs Above Function

In the harbor district of Copenhagen stands a building that simultaneously burns trash and breaks expectations. Officially known as Amager Bakke (but far better known as CopenHill), this waste-to-energy plant slash urban recreation center is one of the most radical and imaginative pieces of architecture of the 21st century.

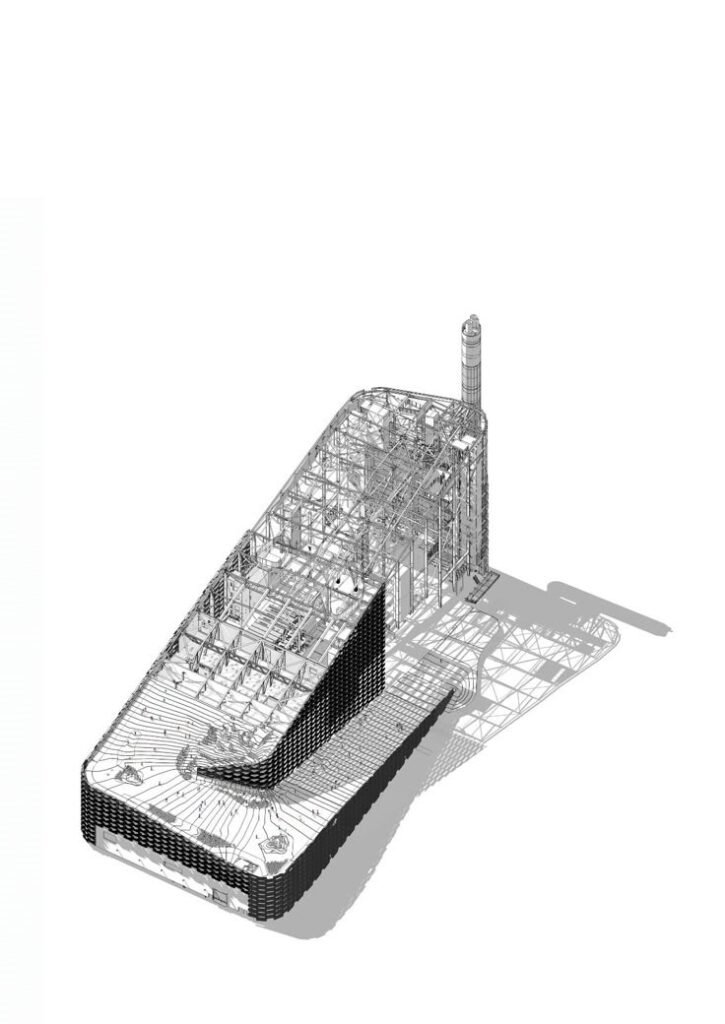

Designed by Bjarke Ingels Group (BIG), in collaboration with SLA (landscape), AKT (structure), and various engineering and environmental consultants, CopenHill is a power plant with a twist—or rather, a slope. Completed in 2019, it converts 440,000 tons of waste annually into clean energy, providing electricity and district heating for around 150,000 homes.

But that’s just the engineering. The architectural magic is this: the building is topped with a 365-meter-long ski slope, a hiking trail, a climbing wall (the world’s tallest), and a rooftop bar all open to the public.

CopenHill is an act of urban alchemy turning garbage into gold, both literally (via energy) and metaphorically (via public experience). Let’s take a walk up the slope and unpack what makes this project not just fascinating, but transformational.

The Big Idea: Hedonistic Sustainability

CopenHill is the embodiment of BIG’s signature concept: “Hedonistic Sustainability.” This idea proposes that sustainability doesn’t need to be about sacrifice it can enhance quality of life.

Instead of hiding the machinery of energy production in an industrial zone far from the public eye, CopenHill invites people to play on it. Why not turn a functional building into a fun one? Why not wrap emissions in experiences?

Bjarke Ingels himself describes the project as “a crystal-clear example of world-changing architecture with a world-changing message.” At CopenHill, sustainability and livability are fused literally climbing over each other.

Site & Context: The Industrial Edge of the City

The site is located on Amager Island, within Copenhagen’s historically industrial harbor district. Traditionally the city’s back-of-house, this area has undergone significant transformation in recent decades much like post-industrial zones in cities across the globe.

But instead of erasing the site’s industrial character, CopenHill celebrates and reprograms it. By integrating recreational and educational programs into a power plant, BIG flips the narrative turning an “undesirable” neighbor into a destination.

From nearby neighborhoods, the green slope of CopenHill rises like a man-made mountain a surreal sight among cranes and chimneys.

Architecture as Infrastructure

CopenHill is a hybrid of building, landscape, and infrastructure. At its core is a waste-to-energy plant designed by engineering firm Ramboll. The industrial core includes:

- Furnaces and boilers that burn waste at high temperatures.

- Steam turbines that convert heat into electricity.

- Air pollution control systems, including filters and scrubbers.

- Flue gas cleaning technology, making the emissions virtually non-toxic.

BIG’s architectural intervention wraps this machinery in a high-performance façade and then uses the envelope to generate public experience.

The Form

The sloping roof is the project’s signature. It’s not a gimmick it’s a landform. At 85 meters high and 10 stories tall, it resembles a geometric ski hill stepped, folding, and functional.

The idea? If you have to build a roof anyway, why not make it useful?

The slope rises gradually, allowing a ski run, hiking trail, and green roof ecosystem to coexist. Accessed by an elevator, stairs, and a funicular-style magic carpet, it leads visitors through a journey from the ground to the summit with stops for leisure, sport, and Instagram selfies.

The Ski Slope: Urban Playground Meets Alpine Ambition

Yes, you can ski on a power plant.

The rooftop ski slope designed in collaboration with snowflex surface provider Neveplast operates year-round without snow, using synthetic turf that mimics the glide of real snow.

There are three runs: beginner, intermediate, and advanced. There’s even a freestyle park with jumps and rails. Visitors rent skis on-site and can enjoy the view of Copenhagen’s skyline as they descend a literal trash burner.

It’s an experience that’s as weird as it is wonderful and a reminder that urban space can be playful, not just pragmatic.

Beyond Skiing: Climbing, Hiking, and More

If skiing isn’t your thing, CopenHill still offers multiple ways to engage.

- Climbing Wall: One façade is clad with the world’s tallest artificial climbing wall an 85-meter-tall vertical challenge with handholds bolted directly onto the building’s surface.

- Hiking Trail: A zigzagging path winds its way up the slope, landscaped with native grasses, wildflowers, and small trees.

- Rooftop Bar and Café: At the summit, visitors can take in views of the Oresund Strait and sip drinks above the smokestacks.

This layering of activity turns CopenHill into a new urban typology half infrastructure, half amusement park.

The Façade: Function and Expression

The building’s façade is a marvel in itself. It consists of 1.2-meter-wide aluminum bricks stacked like oversized LEGOs. These bricks are perforated for ventilation and appear to shimmer in sunlight a high-tech skin that is both industrial and sculptural.

Some panels are operable, allowing maintenance access and natural light. The uniformity of the system contrasts with the irregularity of the green slope above, creating a dialogue between the artificial and the organic.

The idea was to express the building’s massive industrial function without hiding it to make machinery beautiful.

Sustainability in Substance, Not Just Symbolism

CopenHill isn’t just symbolic of green architecture it is green architecture, both literally and figuratively.

Energy Production

- Burns non-recyclable waste from homes and businesses.

- Converts waste into electricity and hot water for the city’s district heating system.

- Has a capacity to handle 150,000 tons of waste per year.

- 99.5% of emissions are filtered before release, making the facility among the cleanest incinerators in the world.

Carbon Footprint

While waste-to-energy is not without criticism (especially from zero-waste advocates), in the Danish context, it’s a highly efficient, interim solution until a full circular economy is realized. Compared to landfilling, it drastically reduces methane emissions and recovers usable energy.

Biodiversity & Ecology

The rooftop landscape, designed by SLA, includes over 300 trees and shrubs, planted in soil beds engineered for drought resistance and urban microclimates. This creates habitat corridors for birds and insects, and softens the hard edges of the plant.

Urban Impact: Rebranding Infrastructure

One of CopenHill’s most profound impacts is cultural.

In many cities, infrastructure is seen as NIMBY (Not in My Backyard). BIG flips this to YIMBY (Yes in My Backyard). Instead of being hidden away, CopenHill becomes a city icon, a tourist destination, a civic space, and a teaching moment.

It also redefines the skyline not with a spire or a tower, but with a sloping green hill that defies categorization.

Through educational tours, youth programs, and public events, the project also raises awareness of the systems that make modern cities function bringing transparency to energy, waste, and climate challenges.

CopenHill in Pop Culture & Global Discourse

CopenHill has appeared in:

- Documentaries on climate change.

- Architecture journals worldwide.

- Ski magazines

- Countless architectural awards circuits.

It’s been celebrated not just as a great building, but as a paradigm shift proof that utility buildings can be beautiful, interactive, and culturally catalytic.

A Blueprint for Future Cities?

CopenHill is not just a one-off spectacle. It raises important questions:

- What if all power plants were also public parks?

- Could sewage treatment plants become wetlands?

- Can utility buildings double as climate education centers?

The project acts as a prototype a speculative diagram brought to life that suggests how infrastructure can become part of the social and spatial fabric of cities, not just hidden beneath them.

Conclusion: Upending Expectations, Literally

At first glance, CopenHill might seem absurd: skiing on a trash incinerator? But once experienced, it becomes obvious: this is what 21st-century architecture should do address climate, society, energy, recreation, and joy all at once.

In a time when many buildings merely comply with codes or chase awards, CopenHill dares to inspire. It’s not about blending in it’s about standing up, speaking out, and sliding down.

From the tip of its chimney to the base of its ski slope, CopenHill embodies a message every city should take seriously:

The future doesn’t have to be grim. It can be green, bold, and maybe even a little fun.