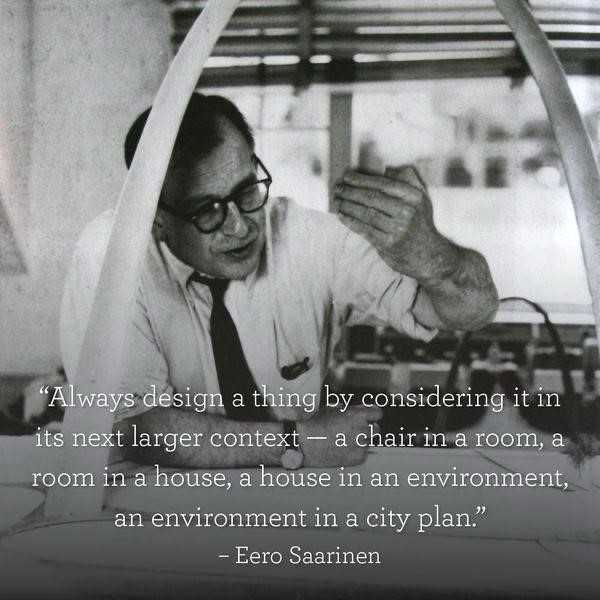

~ Eero Saarinen Eero Saarinen, the Finnish-American architect and industrial designer, left an indelible mark on the 20th century with his bold, often sculptural, and profoundly contextual creations.1 His famous dictum, "Always design a thing by considering it in its next larger context – a chair in a room, a room in a house, a …

~ Eero Saarinen

Table of Contents

- A Chair in a Room: The Object and its Immediate Interior

- A Room in a House: The Interior and its Architectural Framework

- A House in an Environment: The Building and its Natural/Built Surroundings

- An Environment in a City Plan: The Urban Fabric and Beyond

- Implications for Contemporary Architecture

- Conclusion

Eero Saarinen, the Finnish-American architect and industrial designer, left an indelible mark on the 20th century with his bold, often sculptural, and profoundly contextual creations.1 His famous dictum, “Always design a thing by considering it in its next larger context – a chair in a room, a room in a house, a house in an environment, an environment in a city plan,” encapsulates a holistic design philosophy that transcends mere aesthetics.2 It’s a call for designers to understand the intricate web of relationships that define an object or building, ensuring that each element contributes harmoniously to the larger whole. This philosophy argues against isolated design decisions, advocating instead for a cascading consideration of scale, where the smallest detail is informed by the grandest vision.

To truly appreciate the depth of Saarinen’s wisdom, we must unpack each layer of his statement, examining how this principle applies to architectural design and how Saarinen himself exemplified it through his iconic works.

A Chair in a Room: The Object and its Immediate Interior

The journey begins with the smallest scale: a chair in a room. This seemingly simple relationship is the foundational layer of Saarinen’s contextual design. It posits that a piece of furniture is not an isolated entity, but an integral component of the interior space it inhabits. Its form, material, scale, and even its tactile qualities must respond to the room’s function, its aesthetic language, and the human activities it facilitates.

For Saarinen, this wasn’t just about matching styles; it was about creating a cohesive experience. His groundbreaking furniture designs often exemplified this.3 Take, for instance, the Tulip Chair (1956).4 Saarinen’s frustration with the “clutter” of chair legs beneath tables led him to design a single-pedestal base, striving for a sense of unity and fluidity.5 He famously stated, “The underside of typical tables and chairs is a confusing, unrestful world… I wanted to clear up the slum of legs.” This wasn’t merely an aesthetic preference; it was a response to the practical context of a dining room or office space, where multiple legs could create visual chaos and impede movement.6 The Tulip Chair, with its organic, sculptural form, was conceived to integrate seamlessly with the table it accompanied, creating a cohesive furniture group rather than disparate pieces.7 Its smooth, continuous lines and single stem base allow for easy cleaning and a sense of lightness, directly addressing the functional context of a room.

Similarly, the Womb Chair (1948) was designed in collaboration with Florence Knoll, who requested “a chair that was like a basket full of pillows – something I could really curl up in.” Here, the “room” context is not just about visual harmony but about human comfort and the emotional experience within the space.8 Saarinen designed a chair that literally envelops the sitter, offering a sense of security and relaxation.9 Its organic contours and generous proportions respond directly to the human body and the desire for a cozy, inviting nook within a larger room, whether it be a living room or a study. The Womb Chair doesn’t impose itself on the room; rather, it creates a personal sanctuary within it, demonstrating how a piece of furniture can profoundly shape the micro-experience of an interior.

A Room in a House: The Interior and its Architectural Framework

Moving up in scale, Saarinen emphasizes considering “a room in a house.”10 This expands the context to include the interrelationships between different spaces within a single building. A room is not just a box; it is part of a sequence, a network of circulation, and a contributor to the overall spatial narrative of a house. Its size, fenestration, ceiling height, and connection to adjacent rooms or outdoor spaces must be thoughtfully orchestrated to support the flow of life within the dwelling.

Saarinen’s approach to this level of context is evident in his residential projects, though fewer in number compared to his institutional works. While less documented than his larger public buildings, his design of the Irwin Miller House (1953) in Columbus, Indiana, provides an excellent illustration.11 Here, the house is organized around a central, sunken living room that serves as the heart of the home. This “room” is not isolated; it opens onto other spaces – the dining area, the kitchen, and through expansive glass walls, to the meticulously landscaped outdoor environment. The low-slung, flat-roofed design allows for varied ceiling heights that define specific zones within the open-plan interior, creating distinct “rooms” without rigid walls. The relationship between the living room and the surrounding spaces is fluid, reflecting a desire for both openness and defined areas for different family activities. The material palette – brick, wood, and glass – extends seamlessly from interior to exterior, blurring the traditional boundaries of the “room” and integrating it with the larger “house” and even the “environment.”

This integrated approach meant that Saarinen would consider how natural light would penetrate from one room to another, how sound would travel, and how visual axes would connect various parts of the house. Every room was designed not as a standalone entity but as a chapter in the larger story of domestic life, contributing to the overall character and functionality of the home.

A House in an Environment: The Building and its Natural/Built Surroundings

The next leap in scale involves “a house in an environment.”12 This is where Saarinen’s contextual thinking truly begins to manifest on a grand architectural scale. The environment encompasses everything outside the immediate confines of the building: the landscape, topography, climate, natural light patterns, and even the cultural or historical context of the site. A house, or any building for that matter, must engage in a dialogue with its surroundings, responding to existing conditions while also shaping them.

Saarinen’s most celebrated works demonstrate this principle profoundly. The TWA Flight Center (now the TWA Hotel) at John F. Kennedy Airport (1962) in New York, is a quintessential example.13 Here, the “environment” is the dynamic, bustling, and ever-changing world of air travel. Saarinen’s design is a direct response to the energy and symbolism of flight. The terminal’s soaring, concrete shell roof, reminiscent of a bird’s wings or an aircraft taking off, is not merely a sculptural gesture; it embodies the very spirit of its environment.14 It physically connects the terminal to the vast scale of the airport, and emotionally, to the exhilaration of air travel. The building doesn’t just sit in the environment; it is the environment, an architectural manifestation of speed, fluidity, and futuristic aspiration. The interior spaces flow organically, echoing the exterior forms, creating a seamless journey from the arrival gate to the boarding lounge – a truly immersive “tea” experience within a grand “teacup.”

Another powerful example is the Kresge Auditorium (1955) at MIT in Cambridge, Massachusetts.15 Saarinen conceived this building as a complement to the existing neo-classical structures of the campus, yet distinct enough to represent the modern era of MIT. The “environment” here is an academic campus with a specific architectural character and a desire for forward-thinking design. The auditorium’s iconic thin-shell concrete dome is a daring structural feat that responds to the functional need for a large, column-free interior space. Its pure geometric form, while sculptural, also harmonizes with the surrounding open spaces and trees, creating a landmark that is both distinctive and respectful of its academic context. It’s a “house” that acknowledges its neighbors while confidently asserting its own identity.

An Environment in a City Plan: The Urban Fabric and Beyond

The broadest and perhaps most complex context in Saarinen’s philosophy is “an environment in a city plan.” This level requires an architect to think as an urbanist, understanding how individual buildings contribute to the larger urban fabric, its public spaces, infrastructure, and socio-economic dynamics. It’s about designing for the collective good, recognizing that a single building’s impact ripples throughout the urban landscape.

While Saarinen wasn’t primarily an urban planner, his large-scale institutional projects often had profound urban implications. The Gateway Arch (1965) in St. Louis, Missouri, is his most monumental embodiment of this principle. The “environment” here is the entire city of St. Louis, its historical significance as the “Gateway to the West,” and its location on the Mississippi River. The Arch is not just a structure; it is a civic monument, a symbol, and a catalyst for urban renewal. Its soaring, parabolic form, designed to be seen from miles away, stitches together the city with the riverfront, revitalizing a neglected area. It defines a new urban landmark, drawing people to the area and celebrating the city’s unique history. The negative space created by the Arch is as important as its physical form, framing views and shaping the urban vista. It is an element of a city plan that elevates an entire environment, imbuing it with new meaning and purpose.

Another example is the GM Technical Center (1956) in Warren, Michigan.16 While not a “city plan” in the traditional sense, this sprawling complex of interconnected buildings and meticulously planned landscapes functions as a self-contained environment within a larger industrial context. Saarinen designed a campus that fostered innovation and collaboration, creating a harmonious and functional environment for thousands of employees. The repetition of modules, the integration of reflective pools, and the precise landscaping create a sense of order and serenity within a vast industrial setting. The “environment” of the campus was carefully crafted to facilitate its ultimate purpose: the advancement of automotive technology. This project demonstrates how a designer can create a highly specific, functional “environment” that responds to its internal needs while being a significant planned entity within a broader regional context.

Implications for Contemporary Architecture

Saarinen’s holistic design philosophy remains profoundly relevant today, perhaps even more so given the increasing complexity of our built environment.

- Integrated Design Process: His approach advocates for an integrated design process where architects, landscape architects, urban planners, and even industrial designers collaborate from the outset.17 This breaks down disciplinary silos, ensuring that decisions made at one scale are informed by considerations at all other scales.

- Contextual Sensitivity Beyond Style: It moves beyond superficial stylistic matching to a deeper understanding of context – functional, cultural, historical, environmental, and social.18 A building should not just look good; it should perform well within its context, contribute positively to it, and enhance the human experience within it.19

- The Power of Small Details: It reminds us that even the smallest element, like a door handle or a light fixture, has a role to play in the overall narrative of a building and its environment. These details, when thoughtfully designed, can reinforce the larger design intentions and contribute to a cohesive and memorable experience.

- Resilience and Sustainability: Considering a building in its environment, and that environment in a city plan, naturally leads to more sustainable and resilient design. Understanding climatic conditions, local materials, and ecological systems at different scales is crucial for creating buildings and cities that can thrive long-term.

- Urban Cohesion and Identity: In an era of rapid urbanization and often disjointed development, Saarinen’s philosophy offers a framework for creating more cohesive and meaningful urban environments. By thinking about how each building contributes to the street, the neighborhood, and the city as a whole, we can build places that foster a stronger sense of community and identity.

Conclusion

Eero Saarinen’s famous quote is more than just a piece of design advice; it’s a profound declaration about the interconnectedness of all designed things. From the ergonomic curve of a chair to the sweeping gesture of a national monument, every element is part of a larger system.20 His work consistently demonstrated that true architectural excellence lies in this holistic understanding – the ability to see the “chair” not as an isolated form, but as a crucial component within a finely tuned symphony of space, function, and human experience.

Saarinen’s legacy encourages architects to be thinkers, not just form-makers. To understand the “tea” – the life and purpose a “teacup” is meant to contain – and to craft the “teacup” with such precision and contextual awareness that it elevates the human experience within. His buildings, from the quiet dignity of the Kresge Auditorium to the soaring dynamism of the TWA Flight Center and the enduring symbolism of the Gateway Arch, continue to speak eloquently of this integrated vision, reminding us that truly great design is always a conversation between the part and the whole, the object and its universe.