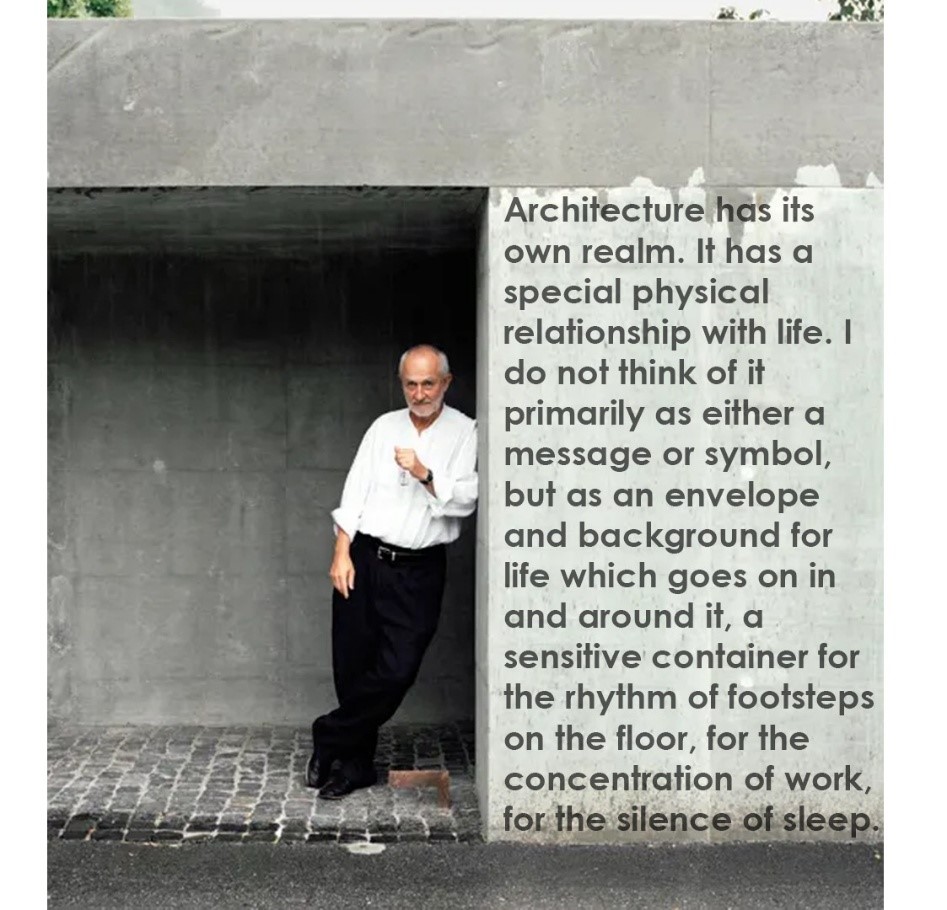

~Peter Zumthor Architecture is often romanticized as a language of symbols, a political tool, or a medium of grand expression. Yet, Peter Zumthor, a master of atmosphere and materiality, reminds us that architecture’s deepest power lies not in its symbolism, but in its intimacy with life. This quote is a profound philosophical statement, emphasizing that …

~Peter Zumthor

Table of Contents

- The Realm of Architecture

- Physical Relationship with Life

- Not a Message or Symbol

- Architecture as Envelope and Background

- A Sensitive Container

- Rhythm of Footsteps, Concentration of Work, Silence of Sleep

- Peter Zumthor’s Built Philosophy

- Implications for Practice and Education

- Relevance in Contemporary Architecture

- Conclusion: Architecture That Listens

Architecture is often romanticized as a language of symbols, a political tool, or a medium of grand expression. Yet, Peter Zumthor, a master of atmosphere and materiality, reminds us that architecture’s deepest power lies not in its symbolism, but in its intimacy with life. This quote is a profound philosophical statement, emphasizing that architecture is not the main act but the stage, the envelope, the container where the drama of human life unfolds. In this essay, we delve into this perspective and explore architecture not as an object of spectacle but as a companion to our daily rhythms.

The Realm of Architecture

Zumthor begins by stating that “architecture has its own realm.” This assertion immediately sets architecture apart from adjacent disciplines like visual art, sculpture, or literature. While these mediums often focus on delivering a message, telling a story, or evoking an emotional reaction from a distance, architecture is immersive and inhabitable. It cannot be fully appreciated in a single glance or through a photograph. It surrounds us, touches us, and reacts to our presence.

This unique realm is both physical and sensory. Architecture deals with space, light, materials, textures, acoustics, and proportions all in real time and physical proximity to the human body. The architect, then, becomes a choreographer of experience rather than a mere form-giver or image-maker.

Physical Relationship with Life

Zumthor highlights architecture’s “special physical relationship with life.” This is not a metaphor it is literal. Architecture houses life. It is the setting for our most mundane and most profound experiences: waking up, making coffee, raising children, grieving, creating, healing, and growing old. Architecture holds all of it.

In our era, much of architecture has been reduced to icons and Instagram moments. The physicality of space its temperature, smell, sound, and surface are often neglected. Zumthor, however, insists that good architecture is rooted in how it physically interacts with our bodies.

He designs not just for the eye, but for the skin, the ears, and the feet. In his Thermal Baths at Vals, the echo of water, the warmth of stone, the filtered sunlight all contribute to an immersive environment where architecture dissolves into sensation.

Not a Message or Symbol

In stating that architecture is “not primarily a message or symbol,” Zumthor pushes back against modernist and postmodernist tendencies to treat buildings as communicative devices. While some architecture certainly carries political, cultural, or ideological symbolism, Zumthor’s interest lies elsewhere.

He is not dismissing meaning; he is prioritizing experience. A building should not be understood like a sentence it should be felt like a presence. When architecture is reduced to symbolism, it becomes didactic and rigid. When it is designed as an atmosphere, it becomes open, inclusive, and alive.

In this light, the architect is not a preacher or a poet, but a composer of spaces that enhance living.

Architecture as Envelope and Background

One of the most profound ideas in this quote is that architecture is an “envelope and background for life.” This modest positioning is deceptively powerful. While much of contemporary architecture seeks to dominate the skyline or capture headlines, Zumthor reminds us of architecture’s humility. It is not the protagonist. It is the setting.

In the same way that a good film score supports but does not overshadow a scene, architecture should frame and support life without overwhelming it. This approach is deeply humanistic. It recognizes that buildings are not art objects; they are shelters, workplaces, sanctuaries, and gathering places.

The best architecture is often the most invisible it allows life to happen effortlessly.

A Sensitive Container

The phrase “sensitive container” is a poetic encapsulation of architecture’s ideal state. Sensitivity here implies responsiveness to context, to climate, to history, and above all, to the human condition.

A sensitive building listens before it speaks. It understands that different activities require different atmospheres. It respects silence, celebrates sound, and embraces change. It is never rigid or indifferent.

For example, a sensitive hospital room might lower anxiety through views of nature, soft acoustics, and warm materials. A sensitive school might stimulate curiosity through flexible, sunlit spaces. A sensitive home offers comfort, privacy, and a sense of identity. These buildings do not scream for attention, but their presence is felt deeply.

Rhythm of Footsteps, Concentration of Work, Silence of Sleep

Zumthor ends his quote with three evocative images footsteps, work, and sleep. These represent the fundamental human rhythms that architecture must accommodate.

1. Rhythm of Footsteps

The rhythm of footsteps is not just poetic it is architectural. The way a space guides, slows, or encourages movement is a crucial part of design. Think of how a narrow corridor compresses pace, or how a grand staircase invites ascension. Materials also matter: cobblestone sounds different from wood, and polished concrete from carpet.

Architecture that acknowledges footsteps creates a dance between the user and the building. It brings tactility and temporal rhythm to the act of walking.

2. Concentration of Work

Spaces of work whether offices, studios, or classrooms must support focus, creativity, and flow. Architecture influences concentration through daylight, acoustics, proportions, and adjacency.

A well-designed workspace minimizes distractions and maximizes potential. For Zumthor, such spaces are not sterile cubicles but carefully composed environments where the mind feels at ease. Texture, warmth, and natural elements help foster deeper engagement and well-being.

3. Silence of Sleep

To design for sleep is to honor vulnerability. Sleep is the most unguarded, intimate activity we engage in, and architecture must protect and support it.

This requires insulation from noise, appropriate lighting, thermal comfort, and psychological safety. Bedrooms, dormitories, and hotels that succeed architecturally are those that make us feel sheltered and secure.

In invoking the silence of sleep, Zumthor emphasizes the architecture of care a space that does not merely exist but envelops.

Peter Zumthor’s Built Philosophy

Zumthor’s own buildings illustrate this philosophy with quiet confidence.

1. Therme Vals, Switzerland

Perhaps his most famous project, Therme Vals is not a building to look at, but to inhabit. The baths are carved into the hillside, using locally quarried quartzite. The sound of water, the dim light, the smell of stone all orchestrate a meditative experience. Here, architecture is a tactile and sensory background for cleansing and contemplation.

2. Bruder Klaus Field Chapel

This small chapel in Germany is made from concrete cast around a framework of tree trunks, which were then burned out. The result is a dark, charred, sacred interior simple, raw, and deeply atmospheric. It supports silence, solitude, and spiritual reflection.

3. Kunsthaus Bregenz

A museum that lets art breathe. Its translucent facade glows softly, and interiors are restrained to the point of invisibility. Art becomes the protagonist; architecture recedes into a sensitive background.

Implications for Practice and Education

Zumthor’s philosophy invites architects to prioritize atmosphere over appearance, and experience over image. This has profound implications:

1. Design Process

Designing architecture as an “envelope” requires empathy, patience, and deep user understanding. Architects must listen more, draw less. They must observe human behavior, test materials, and prototype spatial experiences.

2. Material Choice

Material is not decorative it is experiential. Texture, temperature, smell, and sound are all shaped by material. Zumthor’s work exemplifies how material authenticity leads to emotional resonance.

3. Sustainability

A sensitive building is a sustainable one. It responds to climate, uses resources wisely, and ages gracefully. It is not about green labels but about thoughtful longevity.

4. Urban Design

At the urban scale, Zumthor’s philosophy can inspire more humane cities. Streets, parks, public squares these should be backgrounds for life, not monuments to design ego. They must invite walking, conversation, rest, and play.

Relevance in Contemporary Architecture

In an age dominated by image-driven architecture, where parametric forms and algorithmic skins often take center stage, Zumthor’s human-centric approach is a counterpoint. He brings us back to the essence of what buildings are for to house life, quietly and gracefully.

His work critiques the culture of speed and spectacle. He champions slowness, silence, and depth. In a world craving meaning and connection, his vision feels both radical and essential.

Conclusion: Architecture That Listens

Peter Zumthor’s quote is not just a reflection it is a manifesto. It urges architects to reframe their role not as form-givers or symbol-makers, but as creators of environments that support, comfort, and enhance life.

To see architecture as an envelope and a background is to embrace humility. To treat it as a sensitive container is to embrace responsibility. And to design for the rhythm of footsteps, the concentration of work, and the silence of sleep is to design for humanity.

In this worldview, architecture is not about control it is about care. It is not about the architect’s ego but the user’s experience. It is not static it is alive.

Peter Zumthor teaches us that good architecture doesn’t just look good. It feels right. It sounds right. It ages well. It belongs. It breathes.

And in doing so, it becomes not just a structure but a home for life itself.