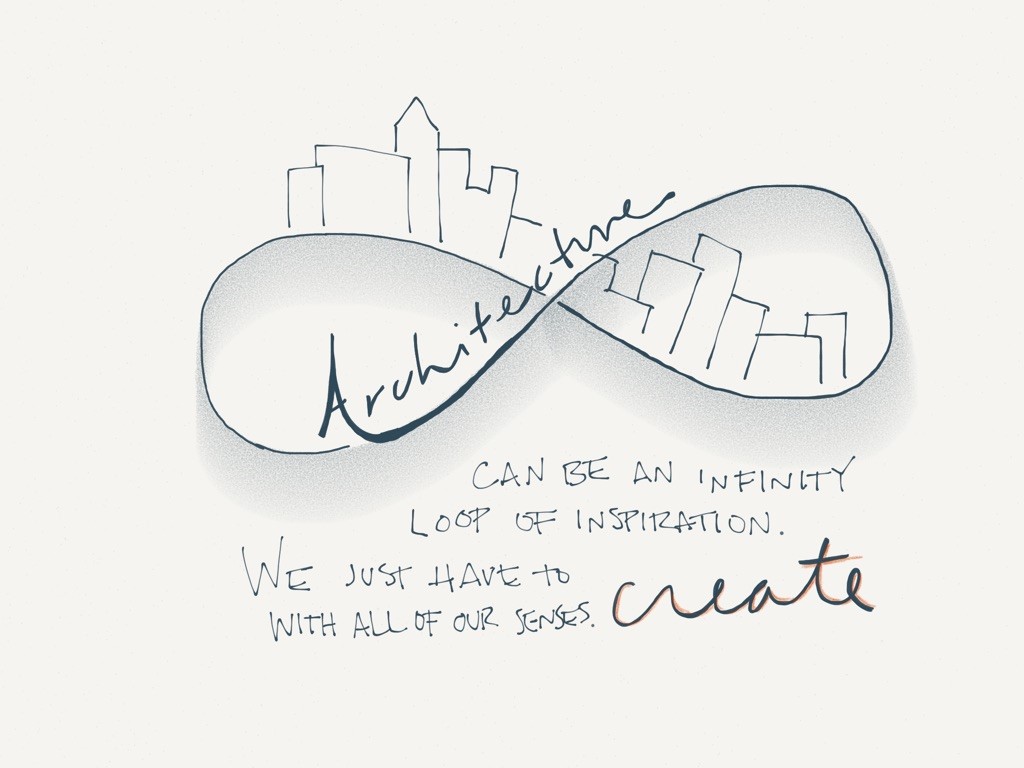

The profound statement, "Architecture can be an infinity loop of inspiration. We just have to create with all of our senses," resonates deeply within the soul of every architect. It is more than a poetic musing; it is a fundamental truth that defines the genesis, evolution, and ultimate impact of every built environment. From the …

The profound statement, “Architecture can be an infinity loop of inspiration. We just have to create with all of our senses,” resonates deeply within the soul of every architect. It is more than a poetic musing; it is a fundamental truth that defines the genesis, evolution, and ultimate impact of every built environment. From the nascent spark of an idea to the lived experience of a completed structure, architecture is a continuous feedback loop, a grand symphony composed not merely for the eye, but for the entirety of human perception. This essay will elaborate on this quote, exploring how inspiration fuels a perpetual cycle of creation, and crucially, why engaging every sense is not just an ideal, but an imperative for truly meaningful architectural practice.

The Infinity Loop of Inspiration: A Perpetual Cycle of Creation

At its core, architecture is an act of transformation – transforming concepts into tangible spaces, challenges into solutions, and aspirations into reality. The quote’s first part, “Architecture can be an infinity loop of inspiration,” speaks to the inexhaustible wellspring from which architectural ideas flow and the cyclical nature of its influence. Inspiration in architecture is rarely a singular, blinding flash; rather, it is an ongoing, cumulative process, a dynamic interplay between the past, present, and future.

Inspiration as a Feedback Mechanism

For an architect, inspiration is both the input and the output. We are constantly absorbing stimuli from the world around us – the historical fabric of a city, the raw beauty of a natural landscape, the innovative spirit of a new technology, or even the nuanced interactions of human beings within a space. This absorption sparks initial ideas. We then synthesize these inspirations, filter them through our knowledge, experience, and creative vision, and translate them into a design. Once this design is built, it ceases to be merely our creation; it becomes part of the shared environment, a new source of inspiration for future generations of architects, artists, and inhabitants. The building itself, through its form, function, and emotional resonance, inspires new interpretations, new needs, and new ways of thinking about space, thus completing and perpetuating the “infinity loop.”

Consider the enduring legacy of Gothic cathedrals. Built centuries ago, their soaring heights, intricate detailing, and play of light continue to inspire awe and inform contemporary design approaches to structure, light, and spiritual space. Similarly, the minimalist clarity of modernism, while a reaction against historical ornamentation, has in turn become a profound source of inspiration for countless buildings that followed, demonstrating how even counter-movements contribute to the loop. Each built structure, successful or otherwise, adds to the collective architectural consciousness, providing case studies, lessons, and springboards for future innovation.

Diverse Wellsprings of Architectural Muse

The sources of architectural inspiration are as boundless as the human imagination. They are not confined to other buildings but span the entire spectrum of human knowledge and natural phenomena:

- The Built Environment: This is perhaps the most obvious source. Studying historical precedents, typologies, construction techniques, and urban planning provides a rich vocabulary of forms, functions, and spatial relationships. Observing how people interact with existing spaces, identifying what works and what fails, becomes invaluable data for new designs.

- The Natural World: Nature is the ultimate architect. Biomorphic forms, the efficiency of natural systems (biomimicry), the play of natural light, the texture of organic materials, the movement of water, and the very climate of a place are inexhaustible founts of ideas. A building shaped by prevailing winds, designed to harvest sunlight, or clad in materials that echo the surrounding landscape, is directly inspired by its natural context.

- Human Experience and Culture: Architecture serves humanity. Understanding social dynamics, cultural rituals, historical narratives, human psychology, and the fundamental needs for shelter, community, and expression is paramount. Designing a school requires inspiration from pedagogical theories and childhood psychology; a hospital from principles of healing and human comfort; a public square from the desire for civic engagement.

- Art, Philosophy, and Abstract Concepts: Beyond the tangible, architecture draws inspiration from the abstract. A piece of music can inspire rhythm and harmony in a façade; a painting, a composition of light and shadow; a philosophical concept, the very essence of a space. Mathematics and geometry provide foundational principles for form and structure, while poetry can evoke emotional qualities that an architect seeks to embody.

- Technology and Innovation: The constant evolution of materials science, construction methods, and digital design tools opens new realms of possibility. The advent of steel and reinforced concrete revolutionized skyscraper design; advanced fabrication techniques allow for unprecedented curvilinear forms; and computational design tools enable complex geometries and performance-driven analyses, continually pushing the boundaries of what can be built.

The architect, then, is a sophisticated receiver, a discerning filter, and ultimately, a powerful generator within this loop. We absorb the world’s myriad inspirations, process them through our unique creative lens, and then manifest them as built form, which in turn feeds back into the global pool of architectural wisdom and experience.

Creating with All of Our Senses: Beyond the Visual Paradigm

The second, and arguably more critical, part of the quote challenges a pervasive tendency in architectural discourse and practice: the overemphasis on the visual. “We just have to create with all of our senses” is a powerful call to embrace a holistic, experiential approach to design, recognizing that human interaction with space is a rich, multi-sensory phenomenon.

For too long, architectural representation – glossy renderings, pristine photographs, and precise plans – has prioritized the visual. While undeniably important, focusing solely on aesthetics risks creating spaces that are beautiful to behold but devoid of genuine life, comfort, or meaning. True architectural quality extends far beyond what meets the eye. It encompasses how a space feels, sounds, smells, and even subtly “tastes” or registers kinesthetically within our bodies.

The Symphony of Senses in Architecture

Let’s dissect how each sense contributes to and must be intentionally designed into the architectural experience:

- Sight:

- Form and Massing: The initial impact of a building’s shape, volume, and silhouette against the sky.

- Light and Shadow: The most dynamic and transformative element. Natural light modulates space, defines surfaces, creates mood, and marks the passage of time. Artificial light extends utility and creates atmosphere. Architects must master daylighting strategies, glare control, and the theatrical potential of illumination.

- Color: Evokes emotion, defines boundaries, highlights elements, and contributes to the overall palette and character of a space.

- Texture and Materiality: How surfaces reflect light, their inherent patterns, and their tactile appearance. This prepares the way for touch.

- View and Vista: The intentional framing of exterior landscapes or interior focal points, creating connections to the outside world or guiding visual narratives within.

- Spatial Relationships: The perceived size, proportion, enclosure, and openness of spaces; how they flow into one another; and how they establish hierarchy and movement.

- Sound (Acoustics):

- Soundscapes: The ambient sounds of a space – whether it’s the quiet hum of a library, the bustling chatter of a marketplace, or the serene silence of a meditation room.

- Reverberation and Absorption: How sounds echo or are absorbed within a space, influencing clarity of speech, musicality, or quietude. Materials like wood, fabric, and concrete all have distinct acoustic properties.

- Noise Control: Designing to mitigate unwanted external noise (from traffic, machinery) or internal noise transmission between spaces.

- The Sound of Materials: The specific sounds produced when interacting with a space – the squeak of a floorboard, the thud of a heavy door, the resonance of a stone wall. These subtle auditory cues contribute to the character and authenticity of a place. Designing for good acoustics enhances focus, communication, and overall comfort, reducing stress and improving quality of life.

- Touch (Haptics and Thermal Comfort):

- Materiality and Texture: The tactile quality of surfaces – the smoothness of polished stone, the warmth of timber, the coolness of metal, the roughness of exposed concrete, the softness of a carpet. These invite physical interaction and provide sensory richness.

- Thermal Comfort: How a space feels temperature-wise. This involves designing for passive heating and cooling, natural ventilation, appropriate insulation, and controlling humidity. A space that is too hot, too cold, or too stuffy immediately detracts from the human experience, regardless of its visual appeal.

- Tactile Feedback: The resistance of a door handle, the spring in a floor, the give of a soft seating area. These physical interactions provide subtle but important sensory feedback.

- Smell (Olfactory Experience):

- Natural Scents: The subtle aroma of natural materials like cedarwood, damp earth, or blooming plants in a courtyard. These can evoke powerful memories and associations.

- Absence of Odor: In some spaces, like hospitals or laboratories, the absence of strong smells is crucial. Effective ventilation and material choices are key.

- Contextual Smells: The faint scent of coffee in a café, chlorine in a swimming pool, or the distinct aroma of old books in a library. While often unintended by the architect, these become part of the place’s identity. Conscious design can enhance or mitigate these. For example, designing a garden space where fragrant plants are strategically placed or ensuring proper ventilation in areas prone to unpleasant odors.

- Taste (Metaphorical and Direct):

- While literal taste buds are rarely engaged in most architectural experiences, this sense can be interpreted metaphorically as the essence or character of a place, its unique “flavor” or “palate.” It encompasses the culmination of all other sensory inputs, creating an overall impression that is internalized.

- Cultural Connection: The “taste” of a place might refer to its cultural specificity, its connection to local cuisine, or the atmosphere it creates for social gathering around food and drink. In a restaurant, for instance, the architecture directly impacts the dining experience, from the lighting that enhances food presentation to the acoustics that facilitate conversation.

- Memory and Association: The “taste” of a space can be deeply tied to memories and emotions. A home might “taste” like comfort and family; a place of worship, like reverence and peace.

- Proprioception and Kinesthesia (Sense of Movement and Spatial Awareness):

- This often-overlooked sense refers to our body’s awareness of its position and movement in space. Architecture profoundly impacts this through:

- Scale and Proportion: How large or small a space feels in relation to the human body.

- Circulation: The deliberate design of pathways, stairs, ramps, and thresholds that guide movement through a building, influencing pace, direction, and discovery.

- Balance and Stability: The sense of groundedness or lightness derived from structural elements and the overall stability of a design.

- Compression and Release: The experiential contrast between narrow, low spaces and expansive, high ones, creating dramatic spatial sequences. A sense of enclosure followed by vast openness.

Designing for the Human Condition

When architects create with all senses, they are not just designing buildings; they are crafting experiences. This multi-sensory approach is profoundly human-centric. It acknowledges that people do not merely observe spaces; they inhabit them, interact with them, and form emotional connections to them.

- Enhanced Well-being: A multi-sensory environment can reduce stress, improve concentration, and promote a sense of calm or exhilaration. Imagine a hospital designed with calming natural light, soothing colors, quiet zones, and access to fragrant gardens – it contributes directly to patient recovery.

- Creating Meaning and Memory: Spaces that engage multiple senses are more memorable and foster deeper connections. The distinct sound of footsteps on a particular floor, the smell of rain on a concrete wall, the warmth of a sun-drenched nook – these imprints combine to form a rich tapestry of memory.

- Accessibility and Inclusivity: Designing with multiple senses is inherently more inclusive. For individuals with visual impairments, tactile and auditory cues become paramount for navigation and understanding. For those with auditory sensitivities, carefully managed acoustics are vital.

- Narrative Potential: Architecture can tell stories. By orchestrating sensory experiences, architects can guide inhabitants through a narrative, creating moments of pause, anticipation, discovery, and reflection.

The Synergy of the Infinity Loop and Sensory Creation

The true power of the quote lies in the symbiotic relationship between its two halves. The “infinity loop of inspiration” is infinitely richer and more potent when that inspiration is gathered and expressed through “all of our senses.” Conversely, the act of “creating with all of our senses” naturally feeds back into the loop, providing more nuanced and profound inspiration for future designs.

An architect who observes the way light rakes across a textured wall (sight), notes the damp, earthy smell after a rain (smell), feels the cool breeze through an open window (touch), and hears the distant murmur of the city (sound), collects a richer, more holistic dataset of inspiration than one who merely sketches the visual form. This detailed sensory observation informs a more sophisticated design process, one that anticipates and orchestrates these layered experiences.

For example, designing a civic building might involve:

- Visual Inspiration: Grand classical facades, modern glass structures.

- Auditory Inspiration: The acoustics of historical assembly halls, the quiet of a library reading room.

- Tactile Inspiration: The solidity of stone, the smoothness of worn railings, the comforting warmth of wood.

- Olfactory Inspiration: The freshness of a naturally ventilated space, the clean scent of polished surfaces.

- Kinesthetic Inspiration: The deliberate procession through a sequence of public and private spaces, the feeling of ascension on a grand staircase.

By integrating these diverse inspirations, the architect designs a space that not only looks impressive but also feels welcoming, sounds appropriate for its function, is comfortable to inhabit, and guides occupants intuitively. This holistic creation then becomes a powerful new source of inspiration for subsequent projects, deepening the loop.

Challenges, Opportunities, and the Future of Sensory Architecture

Creating with all senses presents unique challenges. Sensory experiences are inherently subjective, making them difficult to quantify and communicate to clients. Measuring the emotional impact of a particular scent or the perfect level of reverberation requires both intuition and increasingly sophisticated tools. Technology, however, is providing new opportunities. Virtual reality and augmented reality allow for more immersive pre-visualization of sensory qualities. Smart materials can respond dynamically to environmental conditions, adjusting light, temperature, and even sound. Computational design can simulate complex environmental behaviors, enabling architects to predict and fine-tune sensory outcomes.

The imperative to create with all senses also aligns with the growing emphasis on sustainability and biophilic design. Naturally lit and ventilated buildings, those using local, sustainable materials, and those connecting occupants to nature often inherently provide richer sensory experiences – the sound of rain, the smell of wood, the varied temperatures, and the shifting light. This approach is not merely aesthetic; it is deeply ecological and promotes human health and well-being.

In conclusion, the quote “Architecture can be an infinity loop of inspiration. We just have to create with all of our senses” serves as a guiding principle for the contemporary architect. It reminds us that our profession is a continuous journey of learning, observing, and reinterpreting the world. By consciously engaging all our senses – sight, sound, touch, smell, and the often-unspoken senses of taste and proprioception – we move beyond mere form-making to the profound art of crafting experience. When inspiration is drawn from a multi-sensory engagement with the world, and translated into spaces that resonate with the full spectrum of human perception, architecture transcends its physical boundaries. It becomes a living, breathing entity that truly enriches life, perpetuating an endless cycle of beauty, meaning, and inspiration for all who encounter it. This is the true essence of architecture: a dynamic, evolving dialogue between humanity, nature, and the built environment, felt and understood through every fiber of our being.