~Francis Kere Architecture often carries an image of steel, glass, and extravagant budgets, but the work of Diébédo Francis Kéré proves that true innovation begins with humility, earth, and people. Kéré, a Burkinabé-German architect, has reshaped the global understanding of what it means to design for the future by returning to the basic’s local materials, …

~Francis Kere

Table of Contents

- From Gando to Berlin: A Journey Shaped by Necessity

- The Gando Primary School: A Prototype for a New Kind of Architecture

- Philosophy: Climate, Material, and Community

- Signature Projects: From Villages to Global Stages

- Gando Library and Secondary School (2012–2016)

- Léo Surgical Clinic and Health Centre (2014)

- Burkina Institute of Technology, Koudougou (2020)

- Startup Lions Campus, Kenya (2021)

- Serpentine Pavilion, London (2017)

- Beyond Africa: A Global Voice for Sustainable Architecture

- Recognition and Legacy

- Why Kéré’s Vision Matters Today

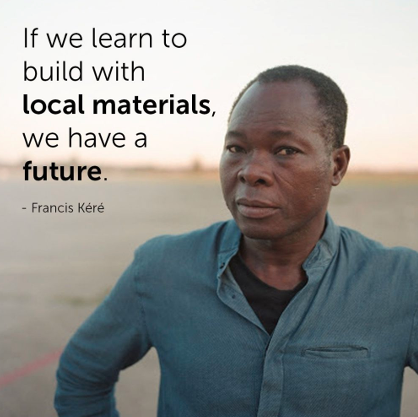

Architecture often carries an image of steel, glass, and extravagant budgets, but the work of Diébédo Francis Kéré proves that true innovation begins with humility, earth, and people. Kéré, a Burkinabé-German architect, has reshaped the global understanding of what it means to design for the future by returning to the basic’s local materials, climate-conscious forms, and deep community involvement. Awarded the 2022 Pritzker Prize, he became the first African-born architect to receive the profession’s highest honor, signaling a shift in the conversation about where groundbreaking design truly originates.

His statement, “If we learn to build with local materials, we have a future,” captures not only his architectural ethos but also a larger vision for sustainability, empowerment, and cultural pride. In an era when construction is responsible for vast energy consumption and carbon emissions, Kéré’s approach feels both timeless and revolutionary. This essay examines his journey, design philosophy, notable projects, and the wider implications of his work for the future of architecture.

From Gando to Berlin: A Journey Shaped by Necessity

Francis Kéré’s story begins in the small village of Gando, Burkina Faso, in 1965. The son of the village chief, Kéré was the first child from his village to attend school. The nearest school was kilometers away, and the classrooms were rudimentary, hot, and uncomfortable. This early experience planted the seed for his later obsession with making educational spaces not just functional, but dignified and comfortable.

In the early 1980s, Kéré received a scholarship to study in Germany, first as a carpenter and then as an architect at the Technische Universität Berlin. His studies exposed him to modern construction techniques, yet he remained acutely aware of the disparities between the sleek, energy-intensive buildings of the West and the basic, climate-challenged structures of his homeland. Rather than abandon his roots, Kéré found inspiration in them, envisioning an architecture that could bridge tradition and modernity while remaining sustainable and affordable.

The Gando Primary School: A Prototype for a New Kind of Architecture

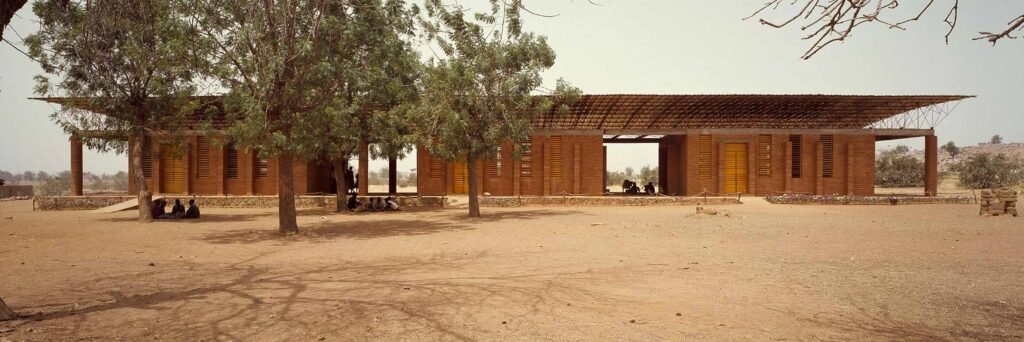

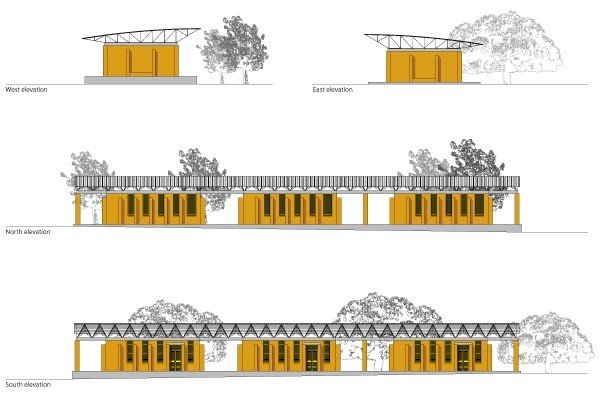

Kéré’s first project, the Gando Primary School, completed in 2001 while he was still a student, was a radical experiment in context-driven design. Instead of importing costly materials or machinery, he relied on what was readily available clay from the earth, sand, and laterite. By stabilizing clay bricks with small amounts of cement and combining them with a raised corrugated metal roof, he created a structure that was naturally cool, durable, and economical.

The building was constructed by the very people it would serve. Kéré trained local villagers in brick-making and building techniques, transforming construction into a collective act of empowerment. The school quickly became more than a building it was a source of local pride, a place of learning not just for children but for the entire village.

The Gando School earned the Aga Khan Award for Architecture in 2004, but more importantly, it became the foundation for Kéré’s career-long approach: architecture as a collaborative, climate-responsive craft.

Philosophy: Climate, Material, and Community

Kéré’s work can be distilled into three interwoven principles:

1. Building with Local Materials

For Kéré, materials are not just a means to an end; they are the soul of a building. He sees clay, laterite, and timber not as signs of poverty but as intelligent, renewable resources perfectly suited to their environment. These materials, when used with thoughtful engineering, provide insulation, durability, and aesthetic warmth.

2. Designing for Climate

Kéré’s projects are masterclasses in passive design. Thick earthen walls create thermal mass, absorbing heat during the day and releasing it at night. Raised roofs and generous eaves funnel cooling breezes and provide shade. Courtyards, perforated walls, and vented ceilings allow hot air to escape naturally. These techniques minimize the need for mechanical systems, making his buildings resilient and energy-efficient.

3. Involving the Community

Kéré believes that people must be active participants in shaping the spaces they inhabit. By engaging locals in every phase—from design to brick production to construction he ensures the buildings are not just functional but deeply cherished. This participation fosters skills, ownership, and maintenance long after the architect has left.

As Kéré often states, “Only those who are involved in the creation of something will care for and protect it.”

Signature Projects: From Villages to Global Stages

While Gando remains the touchstone of Kéré’s philosophy, his portfolio spans schools, health centers, cultural pavilions, and monumental civic projects across Africa, Europe, and beyond.

Gando Library and Secondary School (2012–2016)

These expansions built upon the original school’s success. The library’s design integrates natural light through clay pot skylights, while latticed eucalyptus screens filter sunlight and air. The secondary school employs underfloor cooling systems and strategic landscaping, reducing interior temperatures dramatically even in the Sahel’s scorching heat.

Gando Library and Secondary School

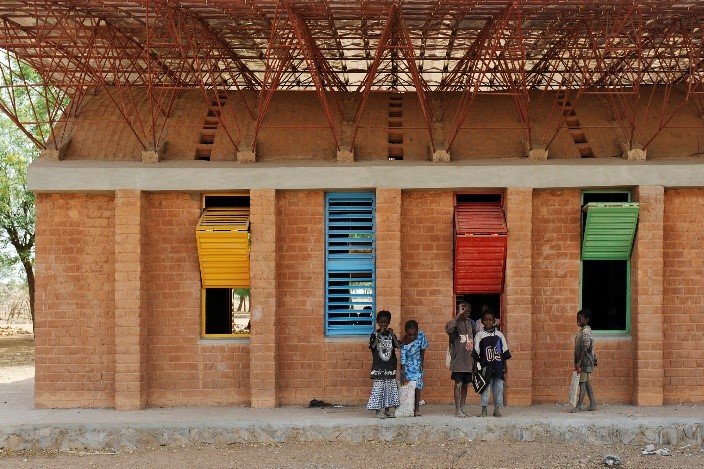

Léo Surgical Clinic and Health Centre (2014)

Located in Burkina Faso, this medical facility uses rammed earth and laterite, with wide, shaded corridors that double as social spaces. The bright, colorful fenestrations serve both aesthetic and functional roles, catering to patients at various postures lying, sitting, or standing.

Léo Surgical Clinic and Health Centre

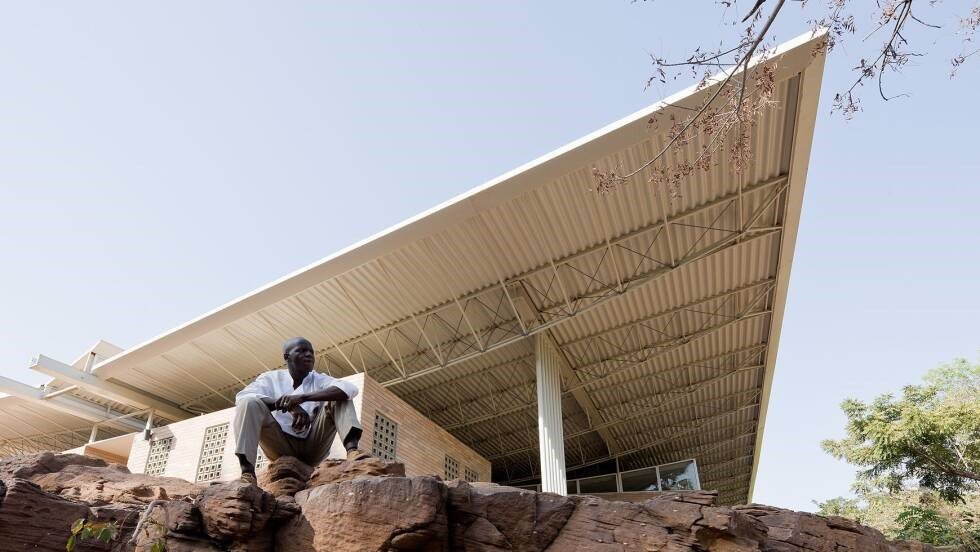

Burkina Institute of Technology, Koudougou (2020)

This project fuses education with environmental stewardship. Its classrooms use cast-in-place earth walls and ventilated roofs, while harvested rainwater sustains surrounding mango trees, creating a campus that is both productive and inspiring.

Burkina Institute of Technology, Koudougou

Startup Lions Campus, Kenya (2021)

Drawing inspiration from termite mounds, this technology campus features cooling chimneys that regulate temperature without mechanical systems, protecting delicate electronics while demonstrating biomimicry at its finest.

Startup Lions Campus, Kenya

Serpentine Pavilion, London (2017)

Kéré’s temporary pavilion in London’s Kensington Gardens showcased how his ethos can transcend climate and culture. Its circular, tree-inspired canopy and open-air structure brought a touch of African communal space to a European audience.

Serpentine Pavilion, London

Beyond Africa: A Global Voice for Sustainable Architecture

Although deeply rooted in African contexts, Kéré’s principles resonate worldwide. His pavilions, installations, and cultural centers demonstrate that local materials and community-driven design are not constraints but opportunities for innovation. His projects in Germany and the United States show how the same approach thoughtful ventilation, tactile materials, human-scale spaces can enrich even the most developed contexts.

Recognition and Legacy

Kéré’s work has earned numerous awards, culminating in the 2022 Pritzker Architecture Prize. His recognition represents more than personal achievement; it signals a paradigm shift in the values celebrated within architecture. No longer is innovation measured solely by technological spectacle or monumental scale, but by how well a building serves its people, place, and planet.

His legacy is twofold: the tangible impact of his projects, schools, clinics, and cultural centers that uplift their communities and the inspiration he provides for architects and students worldwide to rethink what “progress” looks like in design.

Why Kéré’s Vision Matters Today

In an era of escalating climate change, rapid urbanization, and growing inequality, Kéré’s philosophy feels prescient. By prioritizing local materials, passive systems, and community participation, he offers a model for architecture that is environmentally responsible, economically viable, and socially inclusive.

His approach suggests that the future of architecture will not be dictated solely by megacities or high-tech labs, but also by villages, workshops, and communities willing to rediscover the wisdom beneath their feet.

Francis Kéré’s career is a testament to the power of simplicity, collaboration, and rootedness in architecture. From the clay bricks of Gando to pavilions on the world stage, his work proves that architecture can be both humble and transformative. His philosophy challenges architects, planners, and communities everywhere to reconsider the materials, methods, and relationships that shape our built environment.

As Kéré himself reminds us, “If we learn to build with local materials, we have a future.” His words echo beyond Burkina Faso, offering a blueprint for a world where buildings are not just shelters, but symbols of dignity, sustainability, and hope.