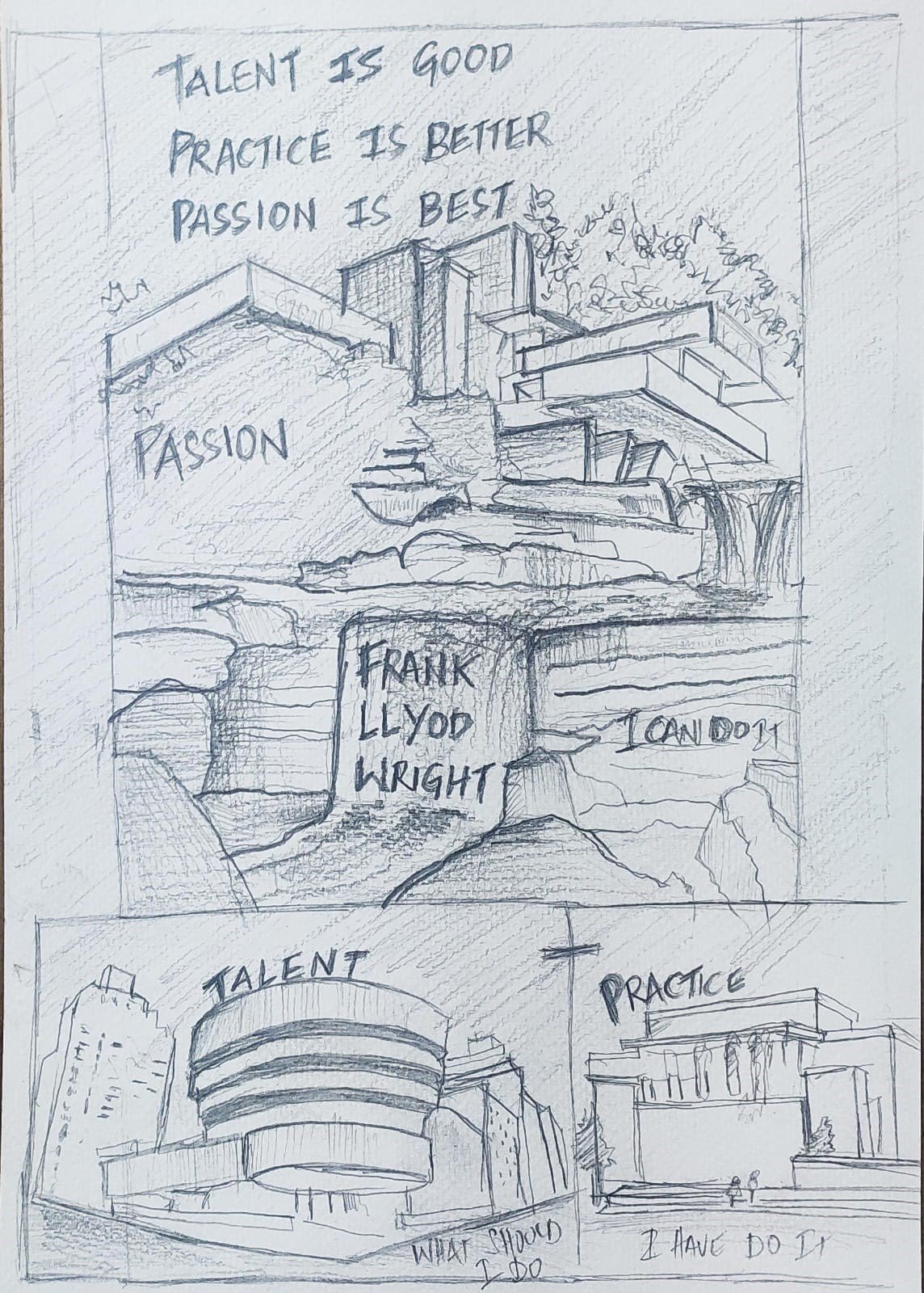

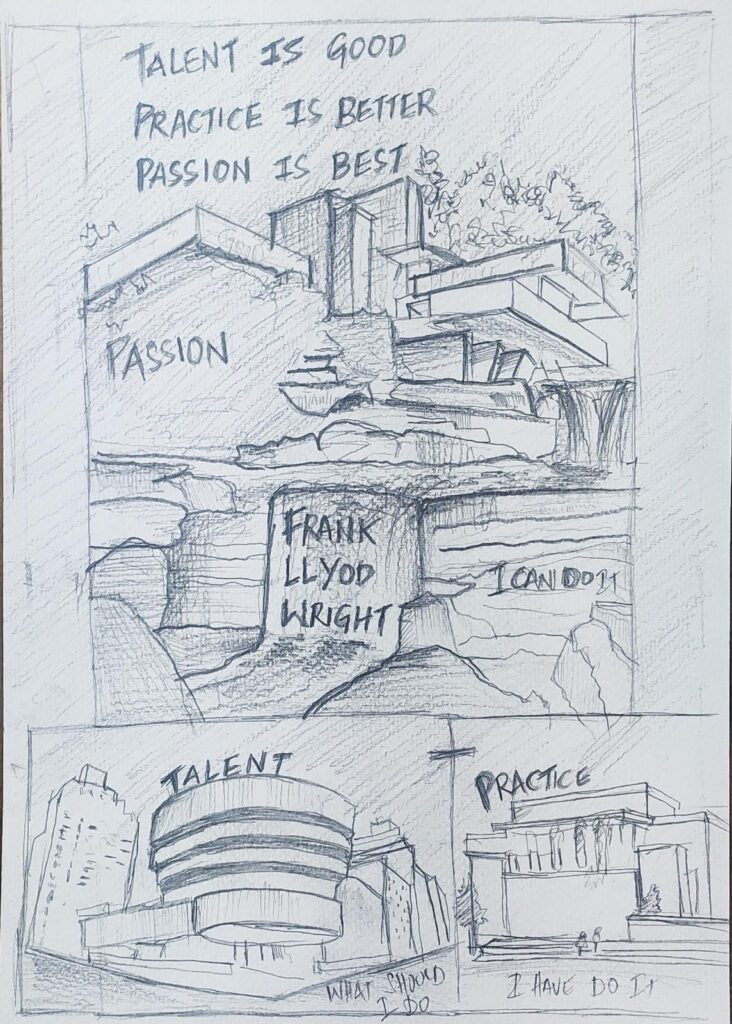

~Frank Lloyd Wright Frank Lloyd Wright, one of history's most influential and visionary architects, left behind not only a staggering portfolio of revolutionary buildings but also profound insights into the nature of creativity and mastery. His concise yet potent declaration, "Talent is Good, Practice is Better, Passion is Best," distills a fundamental truth applicable to …

~Frank Lloyd Wright

Table of Contents

- “Talent is Good”: The Innate Spark

- Manifestations of Architectural Talent:

- The Value and Limitations of Talent:

- “Practice is Better”: The Grinding Wheel of Mastery

- The Architect’s Regimen of Practice:

- “Passion is Best”: The Unquenchable Fire

- The Role of Passion in Architecture:

- The Synergy: Talent, Practice, and Passion Interwoven

- Frank Lloyd Wright: The Embodiment of the Philosophy

Frank Lloyd Wright, one of history’s most influential and visionary architects, left behind not only a staggering portfolio of revolutionary buildings but also profound insights into the nature of creativity and mastery. His concise yet potent declaration, “Talent is Good, Practice is Better, Passion is Best,” distills a fundamental truth applicable to any demanding discipline, but resonates with particular depth within the field of architecture. For an architect, this quote is a roadmap to excellence, underscoring that innate ability is merely a starting point, diligent work is the means to proficiency, but an unquenchable inner fire is the ultimate differentiator and sustained driving force.

Let us unpack this wisdom from the architect’s perspective, exploring how each element contributes to the journey of shaping the built environment.

“Talent is Good”: The Innate Spark

“Talent” in architecture refers to an innate aptitude, a natural inclination, or a predisposition towards certain skills and ways of thinking that give an individual a head start. It’s the raw material, the genetic lottery ticket that provides a foundational advantage.

Manifestations of Architectural Talent:

- Spatial Intelligence: The ability to visualize and manipulate three-dimensional forms in the mind, to understand relationships between spaces, and to conceive complex structures before they are built. This is often the most intuitive and foundational talent for an architect.

- Aesthetic Sensibility: An inherent eye for beauty, proportion, harmony, and composition. It’s the ability to intuitively grasp what “looks right” or “feels balanced.”

- Problem-Solving Acumen: A natural knack for dissecting complex problems into manageable parts and devising creative, efficient solutions. Architecture is inherently about solving intricate puzzles involving function, structure, context, and human needs.

- Drawing and Visual Communication: While technical drawing skills can be learned, a natural flair for sketching, rendering, and communicating ideas visually can be a significant talent. This allows for quick ideation and expression of concepts.

- Empathy and Observation: An innate ability to observe human behavior, understand social dynamics, and empathize with the needs and experiences of future inhabitants. This talent allows an architect to design spaces that truly serve people.

The Value and Limitations of Talent:

Talent is undoubtedly “good.” It makes the initial learning curve less steep, provides a quick grasp of complex concepts, and allows for moments of intuitive brilliance. A talented student might quickly master drafting techniques, envision elegant structural solutions, or intuitively arrange spaces in a pleasing manner. It can open doors and gain early recognition.

However, talent alone is a fertile but uncultivated field. It represents potential, not accomplishment. Without nurture, discipline, and sustained effort, raw talent often stagnates or manifests as unrealized promise. History is replete with individuals who possessed immense natural gifts but lacked the discipline to hone them into mastery. In architecture, a field that demands both artistic vision and rigorous technical execution, relying solely on talent is a recipe for half-baked ideas and unrealized visions.

“Practice is Better”: The Grinding Wheel of Mastery

If talent is the raw gem, “practice” is the relentless, methodical grinding and polishing that transforms it into a brilliant, multifaceted jewel. “Practice is Better” because it is the active pursuit of skill, knowledge, and discipline. It is the bridge between nascent ability and true proficiency.

The Architect’s Regimen of Practice:

Practice in architecture is far more than rote repetition; it’s a multi-faceted, continuous process of learning, applying, failing, and refining.

- Formal Education and Foundational Knowledge: Years of intensive academic study form the bedrock of an architect’s practice. This includes:

- History and Theory: Understanding architectural precedents, philosophical underpinnings, and stylistic evolutions provides context and vocabulary.

- Building Science and Technology: Mastering structural principles, material properties, environmental systems (HVAC, lighting), and construction methods is non-negotiable.

- Design Studios: This is the core of architectural education, where students repeatedly engage in the design process, from conceptualization to detailed resolution, receiving rigorous critique and iterating on their ideas. This constant cycle of design-review-redesign is intense practice.

- Apprenticeship and Professional Experience: After academia, the professional world offers a new realm of practice. Working under experienced architects, interns learn the practicalities of client management, code compliance, project coordination, construction administration, and the nuances of turning designs into built reality. Every project, every site visit, every drawing set is a form of practice.

- Drawing, Sketching, and Modeling: These are the daily exercises of an architect. Whether by hand or digitally, the act of drawing and building models is a form of continuous practice, refining spatial understanding, observational skills, and communication abilities. Wright himself emphasized the importance of drawing as thinking.

- Learning from Failure and Iteration: Every design project involves setbacks, budget constraints, technical challenges, and moments when ideas don’t translate as expected. Practice means embracing these “failures” as invaluable learning opportunities, iterating on designs, and adapting to unforeseen circumstances. It builds resilience and problem-solving muscle.

- Continuous Learning and Adaptation: The architectural landscape is constantly evolving with new materials, technologies (BIM, parametric design, AI tools), sustainability imperatives, and building codes. An architect who stops practicing (i.e., stops learning and adapting) quickly becomes obsolete. Attending seminars, reading journals, visiting new buildings, and experimenting with new tools are all forms of continuous practice.

“Practice is Better” because it translates potential into tangible skill. It builds the endurance to tackle complex projects, the precision to detail intricate connections, and the wisdom to anticipate challenges. It’s the disciplined effort that allows an architect to execute their vision, moving from “good ideas” to “well-built realities.”

“Passion is Best”: The Unquenchable Fire

If talent provides the spark and practice builds the engine, then “passion” is the fuel that keeps the engine running, even through the most arduous journeys, and propels it towards true innovation and enduring impact. “Passion is Best” because it is the intrinsic drive, the deep-seated love for the craft, and the unwavering commitment that transcends mere skill or duty.

The Role of Passion in Architecture:

- Sustained Perseverance: Architecture is a notoriously demanding profession, characterized by long hours, complex challenges, intense client pressures, budget constraints, and sometimes, public criticism. Without genuine passion, the grind of practice can become soul-crushing, leading to burnout or mediocrity. Passion provides the resilience to push through setbacks, find solutions to seemingly intractable problems, and remain dedicated to a vision, even when others doubt.

- Fuel for Innovation and Risk-Taking: True innovation rarely comes from a place of comfort or routine. It requires a passionate belief in a better way, a willingness to challenge conventions, and the courage to take calculated risks. Architects driven by passion are not content with merely adequate solutions; they strive for transformative ones. This internal drive pushes them to experiment with new forms, materials, and technologies, leading to groundbreaking designs.

- Empathy and Meaning-Making: The most profound architecture is not just functional or beautiful; it resonates with the human spirit. This connection stems from an architect’s passion for improving lives and creating meaningful experiences. Passion translates into a deeper empathy for the end-users, leading to designs that genuinely enhance well-being, foster community, and inspire awe.

- Integrity and Craftsmanship: A passionate architect takes immense pride in their work. This translates into a commitment to integrity, meticulous attention to detail, and an unwavering pursuit of craftsmanship, even in unseen elements. They see their work as an extension of themselves, a lasting contribution to the world.

- Inspiration and Leadership: Passion is contagious. A deeply passionate architect can inspire their entire team – designers, engineers, contractors, and clients – to commit fully to a shared vision, fostering a collaborative environment where excellence thrives. They become visionaries who can articulate not just what to build, but why it matters.

Passion transforms work from a job into a calling. It infuses purpose and joy into the demanding journey of creation. It’s the difference between merely designing a building and creating a lasting legacy.

The Synergy: Talent, Practice, and Passion Interwoven

While each element is valuable, their true power lies in their synergy. They are not discrete stages but interconnected forces that continually reinforce one another.

- Talent as the Ignition: Talent provides the initial spark, making it easier to begin the journey and achieve early successes, which in turn can fuel nascent passion.

- Practice as the Amplifier: Practice refines raw talent, turning intuition into repeatable skill and vague ideas into precise constructs. It equips passion with the tools and techniques necessary for realization. Without practice, talent remains potential, and passion lacks the means to manifest its grandest visions.

- Passion as the Perpetual Motion: Passion provides the enduring motivation to engage in relentless practice, especially when faced with frustration or failure. It drives the continuous learning necessary to stay relevant and pushes the boundaries of what talent alone could achieve. It ensures that the architect never settles for “good enough” but constantly strives for “best.”

An architect with immense talent but no passion will likely produce technically proficient but soulless structures. An architect with abundant passion but insufficient practice might generate exciting ideas that never translate into buildable, functional, or elegant forms. It is the harmonious integration of all three—talent providing the aptitude, practice building the skill, and passion igniting the will—that leads to true architectural mastery and enduring impact.

Frank Lloyd Wright: The Embodiment of the Philosophy

Frank Lloyd Wright himself epitomized this very philosophy throughout his long and tumultuous career.

- Talent: Wright clearly possessed an almost unparalleled spatial genius and an innate understanding of materials and form. His early sketches and conceptual ideas often revealed an intuitive grasp of architectural principles that set him apart.

- Practice: His rigorous apprenticeship with Louis Sullivan (the “father of modernism” in America) provided a crucible of intense practice, where he learned the discipline of drafting, detailing, and structural logic. Throughout his life, he was a tireless worker, constantly sketching, drawing, and refining his ideas through countless iterations. His continuous experimentation with materials, construction methods (like the textile blocks), and his evolving “organic architecture” philosophy were all forms of relentless practice. He learned from every project, every challenge, and every setback.

- Passion: Above all, Wright was driven by an unyielding passion for architecture. His conviction in his architectural philosophy, even when it led to professional and personal difficulties, was unwavering. He believed architecture was fundamental to life, deeply tied to democracy and nature. This passion sustained him through periods of financial hardship, public scandal, and professional ostracization, driving him to constantly innovate, experiment, and rebuild his career. His relentless pursuit of his ideals, often against strong opposition, is the ultimate testament to the power of his passion.

Frank Lloyd Wright’s concise statement, “Talent is Good, Practice is Better, Passion is Best,” offers a profound blueprint for any aspiring or seasoned architect. It teaches us that while a natural inclination (talent) provides a fortunate head start, it is the disciplined, continuous honing of skills through practice that transforms potential into proficiency. Most importantly, it is the unyielding, deeply personal connection and love for the craft – passion – that provides the essential fuel for perseverance, the courage for innovation, and the ultimate joy in transforming the built environment. In a profession as demanding, complex, and impactful as architecture, possessing all three in abundance is not merely an advantage; it is the very essence of becoming a truly great architect, capable of shaping not just buildings, but lives and legacies.