Memory as a Building Material For architects, the most elusive material is memory. Stone, brick, timber these can be cut, stacked, or poured. But memory the resonance of history, ritual, and collective identity cannot simply be specified in a bill of quantities. And yet, when a city erases its memory, it erases itself. In a …

Table of Contents

Memory as a Building Material

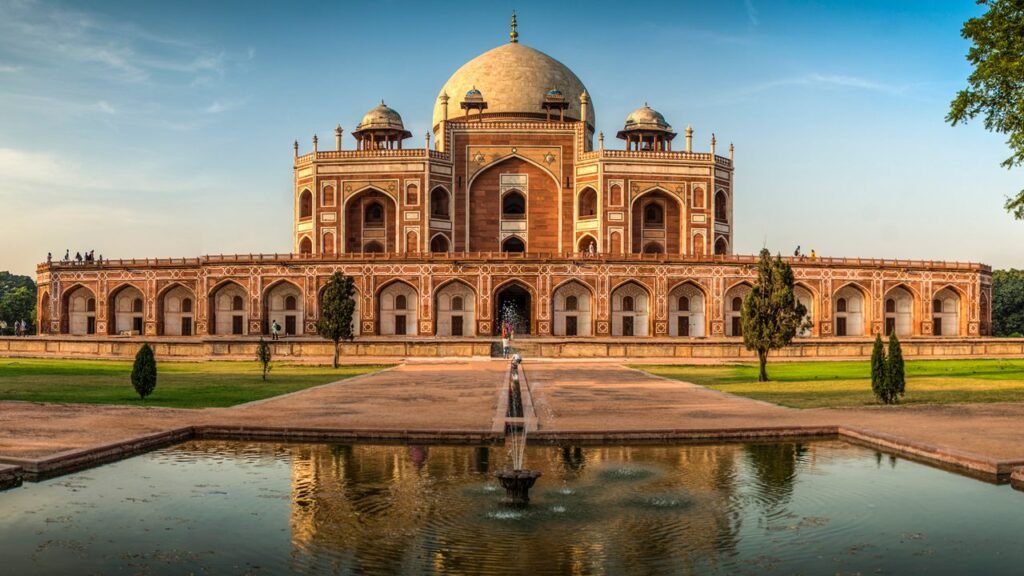

For architects, the most elusive material is memory. Stone, brick, timber these can be cut, stacked, or poured. But memory the resonance of history, ritual, and collective identity cannot simply be specified in a bill of quantities. And yet, when a city erases its memory, it erases itself.

In a world where urbanization races ahead new skylines sprouting like forests of glass and steel heritage often stands vulnerable, dismissed as inconvenient, unprofitable, or obsolete. The architect, however, sees heritage differently. It is not a frozen relic, nor a burden. It is an active resource: a repository of cultural meaning, spatial intelligence, and material wisdom. Preserving heritage is not about resisting change; it is about guiding change so that cities carry their stories forward.

This essay explores the architecture of memory from an architect’s point of view examining why heritage matters, how it can be preserved and adapted, and what global examples reveal about balancing memory and modernity.

Why Heritage Matters in Architecture

From an architect’s perspective, heritage preservation is not merely about nostalgia. It serves vital roles:

- Cultural Continuity. Buildings carry identity. A bazaar in Istanbul, a temple in Kyoto, or a haveli in Jaipur embodies the ethos of generations. When preserved, these structures root communities in belonging.

- Spatial Wisdom. Vernacular forms evolved in response to climate, geography, and social life. Courtyards, thick walls, jaalis, and shaded verandas are performance-driven lessons. Losing them means losing centuries of research encoded in form.

- Sustainability. Demolishing old buildings wastes embodied carbon. Adaptive reuse often saves more energy and resources than new construction.

- Economic Value. Historic districts attract tourism, foster cultural economies, and boost civic pride. The adaptive reuse of warehouses into creative hubs, for instance, revitalizes entire neighborhoods.

- Human Psychology. Familiar places offer emotional stability. Amid fast-paced change, heritage anchors memory, reducing alienation in rapidly modernizing cities.

The Architect’s Role: Beyond Conservation

For the architect, heritage preservation is not about encasing ruins in glass. It is about designing continuity. This involves:

- Documentation and Analysis. Understanding the cultural, material, and spatial logic of heritage sites.

- Adaptive Reuse. Transforming heritage into living assets libraries, museums, cafes, or co-working spaces.

- Sensitive Interventions. Adding new layers without erasing old ones so buildings tell stories across time.

- Community Engagement. Preservation must serve people, not just aesthetics.

- Integration with Modern Needs. Heritage must coexist with infrastructure, safety standards, and accessibility.

Global Examples: Memory and Modernity in Dialogue

1. The Louvre Pyramid, Paris – I. M. Pei

When Pei proposed a glass pyramid in the courtyard of the Louvre, many called it sacrilege. Yet, by inserting a modern intervention, he clarified the relationship between old and new. The pyramid serves as a gateway transparent, respectful, and functional while allowing the 12th-century palace to breathe. This project demonstrated that heritage is not about resisting contrast, but orchestrating it.

2. Berlin’s Neues Museum – David Chipperfield

The Neues Museum, destroyed in WWII, lay in ruins for decades. Chipperfield’s restoration retained scars of war bullet holes, missing frescoes while inserting contemporary interventions in pale brick and concrete. The result is a palimpsest: old and new coexisting without mimicry. For architects, it sets a benchmark: preservation is about honesty, not pastiche.

3. Adaptive Reuse of Tate Modern, London – Herzog & de Meuron

The Bankside Power Station was an industrial relic. Rather than demolish it, Herzog & de Meuron transformed it into the Tate Modern art gallery. The massive turbine hall became a civic space, while the brick façade was retained as memory. The project revitalized the Southbank area, showing how heritage can power regeneration.

4. Qatar National Museum – Jean Nouvel

Nouvel’s design wraps around the preserved palace of Sheikh Abdullah bin Jassim. Inspired by desert rose formations, the new museum honors tradition by placing it at the center of a futuristic shell. It exemplifies how new architecture can amplify heritage, making it a jewel rather than a backdrop.

5. Cheonggyecheon Stream, Seoul

This is a different kind of heritage: urban ecological memory. Buried under a highway, the ancient stream was uncovered and restored, becoming a linear park. The project not only revived cultural identity but also improved urban ecology. It shows heritage is not only buildings it is landscapes, water systems, and rituals.

6. Hampi and Anegundi, India – INTACH Projects

In India, heritage often suffers from neglect or over-tourism. Yet projects in Hampi and Anegundi demonstrate community-based preservation. By training local craftspeople and reusing traditional methods, these projects balance conservation with livelihood generation, keeping memory alive as a living practice.

7. The High Line, New York – Diller Scofidio + Renfro

An abandoned railway could have been demolished. Instead, it became the High Line, a linear park threading through Manhattan. While not ancient, it embodies industrial heritage. The project illustrates how memory of the recent past can be reimagined as vibrant public space.

8. Palmyra Reconstruction, Syria (On-going)

Destroyed by war, Palmyra represents one of the most challenging debates in heritage: authenticity versus reconstruction. Should ruins be left as memory of loss, or rebuilt for continuity? Architects here face ethical dilemmas about what constitutes preservation in a world of violence.

Approaches to Preserving Memory

- Minimal Intervention. Retain as much as possible, intervene only where necessary (Venice Charter principles).

- Adaptive Reuse. Give buildings new functions while retaining form and identity.

- Layered Design. Insert new architecture alongside old, creating dialogue.

- Living Heritage. Support cultural practices (festivals, crafts, rituals) that animate spaces.

- Digital Preservation. 3D scanning and VR archives safeguard memory even if structures are lost.

Heritage Under Pressure

The architect today faces unprecedented pressures:

- Urbanization. Cities like Mumbai, Lagos, and Jakarta expand rapidly, often sacrificing historic fabric.

- Climate Change. Rising seas threaten Venice, Miami, and island heritage sites.

- Conflict. From Aleppo to Mosul, war devastates heritage.

- Tourism. Excessive footfall erodes fragile sites, turning living heritage into spectacles.

- Globalization. The lure of glass towers risks erasing local character.

In this context, preservation becomes an act of resistance a commitment to cultural resilience.

The Psychology of Memory in Architecture

Architects recognize that memory is not just material but experiential. A narrow lane, a smell of lime plaster, the way light falls in a courtyard these are imprinted in collective memory. When such environments vanish, people feel disoriented.

Preservation thus has psychological stakes:

- Belonging. Residents identify with familiar spaces.

- Continuity. Heritage softens the shock of rapid change.

- Healing. In post-conflict contexts, rebuilding heritage offers symbolic recovery.

Toward a Regenerative Heritage

The architect’s challenge is not to freeze heritage, but to make it regenerative. This involves:

- Blending Old and New. Juxtaposition creates richness like Chipperfield’s Neues Museum or Nouvel’s Doha museum.

- Empowering Communities. Preservation must include local stakeholders, not just international experts.

- Integrating Technology. Tools like BIM, laser scanning, and VR aid documentation, while digital craft allows precision in reconstruction.

- Designing for the Future. Heritage buildings must adapt to climate resilience flood-proofing, adaptive ventilation, renewable energy retrofits.

Conclusion: Memory as Future

For the architect, heritage is not backward-looking. It is forward-looking. Preserving memory gives cities resilience, depth, and identity. Without memory, urban landscapes become placeless, interchangeable, soulless.

Global examples from the Louvre Pyramid to the High Line, from Berlin’s war-scarred museum to India’s living temple towns prove that heritage can coexist with modernity, even enrich it. The architect’s role is to choreograph this coexistence, ensuring that every new layer converses with the old.

Ultimately, the architecture of memory is about designing time. It asks: how can buildings tell stories across generations? How can cities remember, even as they grow? In answering these questions, architects shape not only skylines, but also the continuity of human identity.

For in the end, cities without memory are cities without meaning. And meaning is the true foundation of architecture.